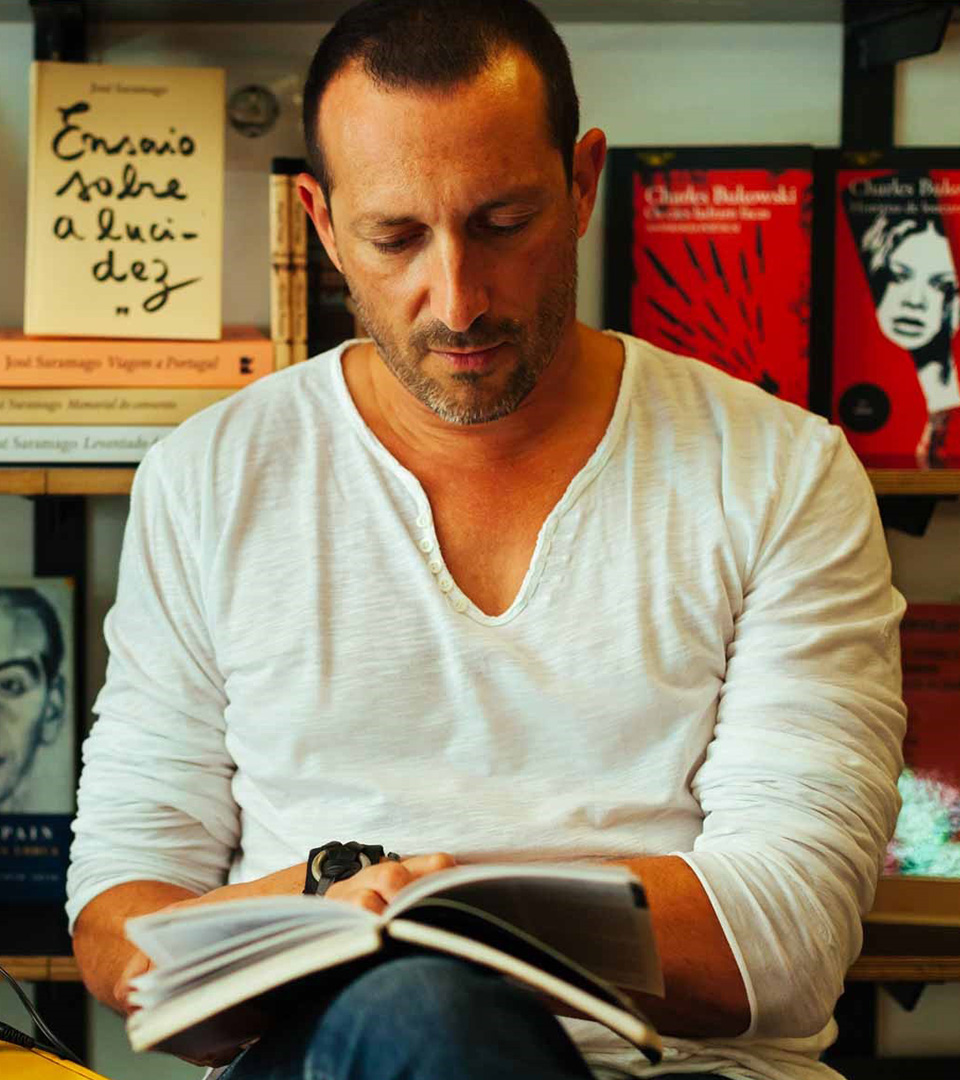

TiagoPereira

Interviewed on 2 July 2019 at Tiago’s home in Lisbon

Memory on the tip of the tongue

Tiago Pereira is the son of a musician, grandson of a matriarch of Beira Baixa, and father of A Música Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (MPGDP), a collection of films of “music and choreography from various genres.” (Translated to English, it means roughly “Portuguese music liking itself,” or “Portuguese Music with a Taste for Itself.”) More than being about music or tradition, MPGDP is about the self-esteem of each person, the memory of all people, and the desire to level the attention. Tiago doesn’t have a driver’s license or paid holidays. He says he doesn’t like fast cars and he gets bored when he’s not working: he suffers from a messianic urgency in what he does – that is, the registration of an oral tradition that will disappear within a few years.

The director ignores the taboos of the foolish and the lame, recording frenetically, without stopping to judge – from Miranda do Douro to Ilha das Flores, placing beloved Portuguese singer-songwriter Conan Osíris on the same level as a series of old ladies and gentlemen who sing to keep themselves company. Countless times, they have already pegged him as the Michel Giacometti of the 21st century, in a comparison with the author responsible for the biggest ethnomusicological collection in Portugal – but this little nickname was exorcised in 2015, in a film by the title “Why I Am Not the Giacometti of the 21st Century.” What can I call him, then? Tiago prefers to introduce himself as “a director who films little old ladies.”

"I’m an activist of collective memory, but I just say that I film little old ladies."

"I record people’s knowledge. I don’t record because it’s traditional, or because it’s no longer traditional."

"We live closer to the Black blues than to the lady who sings in the garden behind our house."

"When people don’t have things planned, they stay, and lose track of time."

"You were there because, yes, you gave time to time. You had time, period."

"Each person, in his or her time, has his or her importance, because each person exists according to the time where he or she is."

"Tradition has always been contemporary. If not, we would be in ancient Rome, using togas and sandals."

"Doing things slowly is sometimes a practice, more than a time in itself."

It’s true that Tiago’s work is focused on music and memory, but if we pay attention, that’s not usually where he points his camera. Our conversation opens with a tight close-up shot, in autofocus mode. “How did you start working with self-esteem?” is what we asked. “From the moment you leave the cities and the highways, and start getting lost in the villages, the first thing you understand is that people think they have nothing to give. You talk about the songs, and they always tell you ‘but I know nothing.’ What does that mean? What does it mean, ‘I don’t know anything good?’ And then I realized that it has everything to do with parameters. Obviously, people have their televisions at home, and they get a lot of their definition of parameters for singing. More and more, you only sing in controlled places, and then people get the idea that to really sing you have to have high heels and makeup and always sing in tune, and have a jury that will evaluate you, because that’s what they see in the shows.”

Does Tiago’s interest in singing, chatting, and aphorisms that people know by heart have this effect of raising self-esteem? “It’s not just interest. What happens is more curious than that. I’d say, ‘Get outta here: I’m more interested in your singing than I am in the television.’ And when I recorded it, I’d put it on the internet right away, and people would start watching it. And these people that they saw were nearby. So there was a kind of local virus, which is to make something viral in just one place. This local virus raises self-esteem and literally increases people’s cognitive abilities. After a day or two, sometimes a week, they’d call me or send a message saying, ‘Come back, I’ve just remembered more!’ – that is, self-esteem also has to do with the cognitive abilities that reinforce everything that really counts. And so, the ladies remember many things…”

MPGDP is such a basic project that it was only a matter of time before it began to diversify, giving rise to La Música Ibérica Queriéndose a Sí Misma (Iberian Music Liking Itself), A Dança Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (Portuguese Dance Liking Itself) and Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (Esporão & Portuguese Cuisine Liking Itself). We asked Tiago if the main objective of this last project was to take gastronomical traditions out of the shadows, and the answer escaped from the parameters of the traditional. “It’s not about traditions, because these days ‘tradition’ is a very complicated word, just like the clichés: heritage, identity, authenticity. There are easy words and difficult words to describe things. Both for Esporão and for MPGDP, I record people, and I record what people know. With the food, I recorded the recipes that people knew about.”

Those who peruse the episodes (22 so far) will discover all kinds of recipes: some passed from great-grandparents to grandparents and from parents to children, others not so much. “There’s a video that I like very much, with two ladies in Évora talking about soup from Beldroegas. One said, ‘Ah, but I don’t put in potatoes,’ and the other said, ‘No no no, I put in potatoes!’ I record people’s knowledge, I don’t record it because it’s traditional or because it’s no longer traditional.”

Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria started in late 2015 with the co-authorship of Chef André Magalhães. Between the cataplana of Litão and Algas, and the caldeirada of Fragateira, there is a series of geographies, regional ingredients, and the sharing of knowledge – from well-known chefs as well as from unknown cooks – always as a sort of voyage of flavors. What dish or snack is indelibly engraved upon the director’s memory? “There’s a soup that my grandmother made, which I’ve been looking for ever since. It was called Santa Teresa soup. It had potatoes, tomatoes and boiled egg. I never saw it again. Sometimes I ask if anyone knows about the soup, but… nothing. I couldn’t find it. I looked once at Maria de Lourdes Modesto, but it had another name and it wasn’t exactly as my grandmother made it.”

We wanted to know if cities kill the roots of things. “I think they create other roots. They don’t kill, they transform. It has to do with times and with cycles, with migrations, and with a certain poverty that was experienced at a certain time in the country in the 20th century. Many people came to Lisbon and forgot their roots, because of the stigma of shame. There is something that gets lost, a certain popular wisdom that you don’t find in university. It’s not the opposite, it’s just another wisdom. You see this shame when you ask where people are from and they don’t tell you the name of the village, they always name the closest city. If you ask someone from Abraveses, they won’t say they’re from Abraveses, but from Viseu. First because people think that no one knows, and then also because of the stigma.”

Tiago remembers a dialogue he heard in Porto, involving wagons, donkeys and two interlocutors. “One of them got angry and said, ‘I don’t agree with anything, none of that.’” (For “none of that” he used the term “nadica,” a very particular old slang of complete negation, something like the English “less than zero” – but stronger, and more colloquial). “Obviously he was from Miranda do Douro and wanted to show that he was proud to say ‘nadica.’ He explained that having a donkey and a cart was as expensive as having a car in Lisbon, that people had to understand how much a donkey and cart cost and that it was not synonymous with poverty.”

Would this shame about that which is rural, or foolish, be linked to the shame of singing in Portuguese? “Of course – it dominated everything. It was a shame of poverty. It was like poverty was something cursed, and you couldn’t show that you were poor, so you got into that logic of the nouveau riche. That’s why you have these emigrants’ houses: you have to show that you’ve been successful in life, that you’ve managed to completely counteract the stigma to which you were somehow condemned. But then there are also other people who came to Lisbon and created roots in Lisbon, with fragments of many other cultures. These are the so-called urban roots, a mixture of everything and something else that you cannot define. There’s an episode at Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa with chef Hugo Brito, and a pork-hearts recipe from Alfredo Saramago’s book Cozinha de Lisboa e Seu Termo, which is a lot of that – it’s the only episode with a completely Lisbon dish, which is exactly what it’s all about. It doesn’t restrict, it doesn’t define the question of what’s traditional, or where it comes from. It opens everything. The heart is studded with cloves, and the cloves came from I-don’t-know-where before they ended up here, and so it’s already a recipe from Lisbon that’s open to all the cultures that are here these days.”

It seems to us that the existence of MPGDP since 2011 has contributed to more people losing their shame of singing and hearing songs in Portuguese. “Nowadays, there’s a lot of information available. You have internet, radio, and television, and much easier access to things. For a long time, you received whatever came to you, and the culture that reigned was Anglo-Saxon. If you were 14 years old with a garage band, you weren’t gonna sing in Portuguese. Usually what you see from new pop or rock groups are imitations of what they like, and then they start to transform. And often, fortunately, they turn into something else and leave the starting point behind. It’s often said – and I’ve said it for a long time – that especially in the big cities in Portugal, we live closer to the Blacks who sang the blues than to the lady who sings in the garden behind our house, or our own grandmother.”

In the context of a bossa nova song, Vinicius de Moraes wrote for so many people to sing: “I’ve danced the twist too much / But I don’t know / I got tired / From calypso to cha cha / I only dance samba / I only dance samba, vai, vai, vai, vai vai…” “We’ve always been closer to this culture because it was this culture that everyone cared about. Then what happened was a discovery of metrics. Which is a bit stupid, because if you notice, you have popular poets who have always composed in tenths, without reading or writing, and who have turned the metrics around even in the logic of tongue twisters. They say very quickly, ‘já disse à mãe do cário que mandasse o carário embora, é cário, é carário, é cário, nós não queremos mais carários agora.’” (Tiago repeats a traditional Portuguese tongue-twister, something with a function comparable to “I wish to wish the wish you wish to wish, but if you wish the wish the witch wishes, I won’t wish the wish you wish to wish.”) “The rhythm of this is very difficult and the old ladies have always used it, but you didn’t see Portuguese singers or musicians picking it up, simply because they didn’t have the knowledge. Even knowing that, Giacometti opened a whole new logic: it was at that time, and for the people of that time. Access to popular music has always been difficult and this is one of the big issues that MPGDP came to resolve: making it easy for the old lady to access Portuguese musical culture, because you can go there and find everything. Before you had some things by Ernesto Faria de Oliveira on the internet, from the University of Minho, which Domingos Morais had put out – but very few people knew about it. Giacometti was very difficult to find, because the full edition of Público by José Moças hadn’t been released yet. There were some videos circulating, almost a kind of pirate radio, with the time codes on top. His audios didn’t exist… Armando Leça was only released in the Alentejo very recently: I don’t know where it had been since 1939! What was Portuguese was always this thing about the miserable condition, the poor little Portuguese who doesn’t invent anything and doesn’t do anything right. There was a lot of that. From the moment you opened the library, you were able to discover other things. [The band] Diabo na Cruz are very important in this sense. When Jorge Cruz starts to make music and records from his library, a whole culture begins to reach other people who probably only ever heard rock music sung in English.” And that’s how Portuguese rock emerges. “I think that from the moment that you have the publishing houses Amor Fúria and Flor Caveira, in the first decade of the 21st century, you have [the band] B Fachada, you have all of that – it has opened up a lot, to the point where we are today, where it’s possible to sing in Portuguese without fear.”

And did the same thing happen in the field of gastronomy? “There was also a denial of traditional products. It had to be a Fausto Airoldi pulling up the sardines, not a Portuguese. When he arrived here, he began to make fine-dining dishes with Portuguese ingredients, and only then did the chefs all start talking about Portuguese products, and you even have that incredible phrase from Alexandre Silva do Loco, which says, ‘For me, Portuguese cuisine is not Alentejo pork with Vietnamese clams and Spanish pork.’ I think that’s what’s pertinent. Like when you play and play the same song many times over – they are actually two very different paths.” Born in Mozambique, Fausto Airoldi spent 30 years in Portugal before leaving for Macau; all of these are destinations with menus written in Portuguese. We’ve already heard of the quest for the long-lost soup, but what about his favorite restaurants? What were the most striking, after so many roads and so many places to film? “Road food is a very complicated thing. Most restaurants outside of Lisbon and Porto have the problem of diversity. Either you have restaurants that are clearly regional, or you’re still stuck with the issue of always having the same steak, the same octopus, the same bacalhau à lagareiro, the rojões à minhota – those meals that they always have – and you don’t move on from there. In addition to always being the same dishes, they’re always the same everywhere, whether you’re in São Pedro do Sul, Fafe or Chaves. In the Alentejo it’s different: you have a lot of regional food and those ex-libris dishes – the sopa de cação, the segredos de porco preto…” But here, two fondly-remembered tascas surge into the conversation – both of them regional, of course. “I remember that I went to Serra da Aboboreira, just near Baião and Amarante, and there was a Tasquinha do Fumo. It was an incredible tasca like that Tasca do Petrol, in Monchique, which is also incredible – they’re two tascas where you eat and you’re like, pffffffff! Sometimes I don’t even remember the names.”

And has the work of chefs and culinary festivals reduced the distance between the product and the plate, between the market and the country? “Yes, of course, but – as hard as it is to hear – that’s only for an elite because it doesn’t reach most people. It exists for those who have money. In Episode 16 of Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar Dela Própria, the chef of Feitoria, João Rodrigues, cooks black pork with green cabbage – in this case, a D.O.C. cabbage because Sr. Domingos (a.k.a. “Mr. Trigger”) comments on why his cabbages, planted in Reguengos de Monsaraz, are different from the others. We quote from the video: ‘the most important thing is for us to know what we are going to eat. If they serve us lettuce, we need to know how it was treated. Sometimes I go to sell at the market and there are people who even say, “over there the guy sells cheaper, I don’t know how much,” and I ask, “and this plant comes from where?” and they say, “don’t know.” But this is what’s important. We’re here, we sow the seeds, we know what we plant and harvest. It puts a big responsibility upon me, to fulfill. I’m not going to do anything else. I’ve been selling in the market since I was 14 years old, I’m now 84… It’s been a few years.” João Rodrigues’s dish pays tribute to one of the most symbolic festivals in Portuguese society – the slaughter of the pigs – and justifies: “people are increasingly distant from their origins and face life in an intense way, with much more speed, very automatically. They have little time to stop. These days, time is almost a luxury – or the greatest luxury of our society.”

Turning back to the man behind the lens: “Often the average consumer doesn’t know where the product comes from. Maybe people should ask more questions. In a restaurant, I don’t know where that octopus, that steak, those pork cheeks come from. It’s still very much a chef thing, but for the people to have that concern, they also need to be at another level which allows them to be sufficiently relaxed to have that concern on an economic level.” And it’s at this moment that we understand: Tiago invented for himself a job that forces him to constantly return to his origins. “It was unintentional. It’s like the Greek myths. When you run away from your destiny, it’s fulfilled. I record traditional music, my father played traditional music… it’s obvious that I’m always returning to my origins. I grew up with my grandmother in Estreito, in Oleiros. My grandmother, her sisters and cousins… the women did everything, took care of their children, protected their husbands, went to the gardens, took care of the animals… They made the pork sausages. The man just put the knife in the pig and then drank with his friends, and then it was the women who would prepare the meat, grill, fry and make the soups. The women always had time to take care of their grandchildren. It wasn’t easy. I managed to get a job that constantly reminds me of this issue, of women. And I still see this – that the actions that have to do with food and caring are done by women. I lived with my grandmother until I was nine years old, but since I was little and until I was 12, I spent three months of every summer in her village. So I have many memories of the village that persist in what I do.”

Unfortunately, the grandson has no memory of his grandmother singing or playing. “I remember my father once going to my grandmother’s house with an adufe, and he left it somewhere. When we went back to get it, she had the adufe in her hand as if she had known how to play it her entire life. But she didn’t play. The truth is that no one would just have a grip like that on an adufe, if they didn’t know how to play it. Things really change a lot, because in Beira Baixa there was a lot of adufe playing. We are witnessing the decline of things. This generation has never experienced the peak and that’s a little sad for me, for what I do.”

In Tiago’s living room, with traditional masks and clay pieces, we can see the poster for the film “Why I Am Not the Giacometti if the 21st Century,” among other pieces – and another, announcing the first musical picnic of MPGDP. “The first was mythical. I don’t think anyone will forget it for a long time. It was in Monforte da Beira. MPGDP had to have a birthday, and I didn’t want a banal party with stage and musicians. Because in November I had been filming in Monforte da Beira and I got along well with the president of the Junta da Freguesia, I told her, ‘Look, I’d like to have a picnic. I have no idea how this is going to happen. I tell people to come, everyone brings their own meal and whatever they want to play, and that’s it.’ After that, it was crazy. Two choirs from Serpa came, two choirs from Viana do Alentejo, a group of drums from Marinha Grande, a group of drums from Alcochete, two groups of women from Minho who sing, people with bagpipes, even Jorge Cruz from Diabo na Cruz… It was suddenly this madness of 600 people singing and dancing, spontaneously, just because they wanted to.” There were many people who took twice as much time to get to the picnic as they were able to be at the picnic. They tried to replicate the spirit of that first picnic for subsequent ones, “but last time we had bad luck because it was raining and we had to go to a pavilion in Viana do Castelo. The last time it was at the Jardim da Estrela and so there were too many exit points, people didn’t stay, because they’d go eat I-don’t-know-where, and disappeared for I don’t know how many hours… When people don’t have things planned, they stay and lose track of time. Nowadays everybody has everything programmed and [at the picnic] there was no plan for anything. A funny thing was the lady from the parish council saying, ‘Ah, I have the SPA here asking what songs we’re going to play,’ but we couldn’t program anything, people would just play whatever they wanted to at the moment. You have this idea of having everything scheduled, you’ll eat at this time and then you’ll do that, and announce it all at the Facebook event that day… But there was nothing planned, nobody knew what was going to happen. You’d come in, eat when you felt like it, and if someone played you could play along, or not. You were there because, yes, you gave time to time. You had time, that’s all. The fertile period was between 13:00 and 17:00, four intense hours.”

And how do you deal with this title of Giacometti of the 21st century? With irony? “It has been worse – I’ve never liked it very much. There’s a time when you realize that each person has their own importance in their time, and that’s a bit of it. Armando Leça has his importance in his time, like Artur Santos, like Giacometti – because it’s a bit impossible to compare people because everything happens in different times. Armando Leça didn’t have electricity. He couldn’t go to the villages. He had a tape recorder that needed to hook up to power, and he had to call the people to come by public transport to the nearest town where there was electricity because most of them didn’t have it. Then Giacometti and Nagra couldn’t go everywhere either. They had a battery-powered, super heavy-duty coil recorder. Nowadays we go with a little tape recorder and a camcorder, we record it, and soon afterward we put it on the internet. Once I recorded Zeca Medeiros in the Azores in the morning. He was going to Faial that day, and by the time he landed, he already had 400 ‘likes’ on the video. And he was like, ‘but what happened? What…?’ Each person, in his time, has his importance, because each person exists within the time where he is. I do that in my time, in the digital age.”

So how does the director and mentor of MPGDP, the “collective memory activist,” introduce himself professionally? “I’m a collective memory activist, but I say that I film little old ladies.” And what does the director of little old ladies and cooks do when he is not working? “I work. I can’t [stop], I get bored. I have to do things. I stop when I’m tired. This is a process of rest that is something else, but for a long time when I stopped I was always aware that someone was dying and I was not filming.” The director comes from a lineage of documentary filmmakers dedicated to recording the oral tradition of people who worked in the fields in the 1930s and 1940s, which is disappearing. “Nowadays, professional actors and singers are the ones who memorize things; other people don’t need them. There’s got to be another tradition which has to do with the digital age, and which will be completely different. Today, no one memorizes 200 songs by heart, because they can find everything on their cell phones. But the little old ladies in the villages can recite 200 poems by memory, without knowing how to read or write. When you meet people who keep the oral tradition alive, obviously you record them… So, when I have time, I also have the notion that this work is urgent, because these people are going to die. We’re talking about 2030 – it’s one more decade.”

So the collection process starts with the elders? “I record the elders, just like I record the youngest. I record the younger ones who have learned from the older ones and who make a point of knowing songs by heart. This story of cante alentejano being Intangible Heritage of Humanity helps to draw in younger people. There are six year olds, ten year olds who sing and do choral groups, and who know these ways. Many of them invent fashions, which is great, because if you do, you know it by heart. It’s all a process of recording what’s disappearing.”

Much of the material that generations of Portuguese learned in school – at least those Portuguese who were born in the first half of the twentieth century – was based upon words and mnemonics. They learned didactic songs and the names of mountains, rivers, and tributaries. Or the main stations of the trans-Siberian railway line that some septuagenarians still have at the tips of their tongues: Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, and Vladivostok. “It comes a lot from Giordano Bruno of the Renaissance, who already had this question of the theater of memory – which, from then on, establishes connections between colors, positions, sites, images, geographies – to remember things. And old people have many tips for remembering things by association. There’s a man I recorded who said, ‘Port wine gives a lot of memory, and has a lot of science.’ Everything that is truly spontaneous has a lot to do with having the right mnemonics, to remember easily what rhymes with what. When they’re under the influence of wine they become looser, and then it’s easier: as they have these mnemonics, they free themselves. They invent I-don’t-know-what and pow, it just sounds right. They are the precursors of hip-hop. This gentleman who was a closeted poet all his life, would come to you and say, ‘look, you want a poem – on what foundation?’” (A foundation is like a motto or a theme, and the poet always gives it a twist.) “You might say, ‘I want one on death,’ and he recites one on death in front of you. ‘I want one on that yellow house,’ and he makes up one on the yellow house.”

Is it also about giving new style to old songs, with the help of contemporary musicians? “Tradition has always been contemporary. If not, we would all be in ancient Rome, using togas and sandals. Everyone has the importance that they have in their own time, and all of this just accompanies time. The tradition that stagnates ends up dying. For example, the caretos of the Ousilhão always had tradition: it’s an initiation rite for boys in the village of Ousilhão, but at a certain point there were no more males being born, so if the women didn’t take on the costume and the caretos, there was no one to do it – they didn’t go into the street, and the tradition died. So they had to accept the transformation of the tradition. In a way, I don’t look for costumes at all. What I seek with my work is to level out the attention. I think that we live in a world obsessed with the attention peaks of television, etc. and that the means of communication do not give importance to all things. Music doesn’t have hierarchies, so I want to give importance to the musician in the philharmonic, as much as to the little old lady who sings alone, or to B Fachada, to Jorge Cruz or to Márcia. That’s why I record everything from Conan Osíris to the little old ladies: because I want people to look at them.”

So your Machiavellian and megalomaniac goal involves recording the millions of Portuguese who sing alone, little old ladies first? “Yes, always recording, because what I’m looking for in MPGDP – and in a way also with gastronomy – is the primordial meaning of things. I want to record the old lady who is cooking and singing to herself. It’s singing in a primordial sense, because everyone has always sung. Nowadays it’s stigmatized: if you sing alone in the street you’re drunk, or crazy. Many years ago, people sang to keep themselves company. They sang just because. Only later did society begin to turn this around. We no longer sing just because. What’s important is to make people sing just because, to sing outside of the controlled environments. That’s what I want to level out: this need to sing.”

And a culinary example emerges: “I remember an incredible video of Esporão with a lady cutting a cucumber just for herself, making a gazpacho that’s just cucumber, water, garlic and a tiny bit of olive oil. But the way she cuts the cucumber without even looking is impressive. In the end, it’s perfectly pulverized. It’s a bit in that sense – you’re always looking for what comes from the origin, whether it’s cooking, singing or dancing.”

What do you think is the memory of a people? Is it very private? “First, we have to define what is ‘a people.’ For me, it’s always in the anthropological sense – it’s individuals. I record the memory of people, so it is more private. It has a lot to do with knowing how to listen to people – nowadays almost nobody knows how to listen. It’s curious that in Lisbon you have the expression, ‘look here’ – but you arrive in the Alentejo and they say, ‘listen up.’ We’re so accustomed to looking, and so little accustomed to listening. I listen to many people. I give them that space where they can be whatever they want. Then I’m there, and I receive, often only after having listened to them for an hour, telling about their illnesses or their misfortunes.”

“We’re talking about ‘going slowly’ here, but sometimes you have to know how to do things slowly in little time. Doing it slowly is sometimes a practice, more than a time in itself. Sometimes you have little time and you can still do it slowly – I do that. I remember Júlio Pereira Pires, an impressive man who has already died. The first time I recorded with him, I took someone from the library in Vila Velha de Ródão who wanted to consult with him, because he could ward off the evil eye. It took him an hour to do the evil-eye, to tell the story of his wife’s illness. This happens all the time, but I never stop the camera.” Tiago is therefore a confidante, a psychologist, and sometimes a borrowed son or grandson. “There’s a very strong social side to MPGDP, which has to do with this exchange. I go there, they give me this, then I distribute what they gave me. They always ask me, ‘Where are you taking me?’ and I say, ‘To the world’ and sometimes the world gives back to them. This process of discovering things in them that they didn’t know they had, is also very important.”

How often do we survive thanks to the generosity of strangers, right? “People are always generous. The happiest man I’ve ever seen in my life lives in Chamarritas, on the island of Pico. He was always completely overjoyed and only said, ‘Guys, let’s go celebrate!’ I recorded with him, and in the end, someone told me that his wife was dying at home. And she died the next day. Sometimes you need to look at yourself in the mirror and ask who you are to deserve such generosity. Who do people stop doing their things, to go and sing for you? Why? Why should it be so?”

Does Tiago have any strategy for living more slowly? Or to avoid being sucked into the nets that steal our attention? “I’m super fast and I hate technology. I don’t have strategies. I really like to walk in order to think. It’s one of those things that I do slowly. I don’t have a driver’s license and I don’t like to travel fast in cars. As for technology, it’s more and more of an economic process rather than a help to life: it makes you a slave dependent upon upgrades and new models, so I try to get away from it.”

Without a driver’s license, it would be impossible for you to do your own projects alone. “Even with a driver’s license it would be impossible. It could never be a solitary job. You always need someone. It’s important to have people with you who haven’t mastered the kinds of things that you record, to allow you to have a certain amount of mental sanity, and not to think that sometimes you’re dreaming – that it’s actually happening. I record people, mostly at the limit of their abilities, and then there are always things that impress you. It’s like Dona Rosário of the Algarve, who’s 103 years old, and plays the concertina. I recorded her when she was 99, and it was really powerful. Her daughter said that Dona Rosário woke up in the middle of the night and played the concertina alone. A 103-year-old lady addicted to concertina? Sometimes you need to pinch yourself, to prove to other people that you’re not crazy, that something like this really does have an unassailable human force – otherwise you’ll get used to living in a bubble and you think it’s all like that.”

How do you teach someone not to find something lame? “Discussing taste. People these days are always discussing what is good or bad. This doesn’t make sense, in terms of music. For example, the whole controversy with Conan Osiris: ‘That’s horrible, that’s bad, he sings badly…’ We have to be great musicians, to know everything about frequencies, about all notes, to have absolutely distinguished ears to be able to define whether he sings well or badly. We don’t know, though – these parameters don’t exist to actually define who sings well. To understand why we like him or why we don’t, we have to disassemble taste. How did you grow up? Where did you grow up? Who did you run with? What did you hear? With whom did you listen? What did you eat? And then you start to understand and disassemble what made you like certain things, and maybe you’ll be more open to enjoying other things, and understanding other things. The only thing we can really discuss is taste. Everything else, you can’t. It’s silly to say that taste is not to be discussed. No – you can only discuss taste. The rest you can’t discuss because it’s too concrete to discuss. There are things that are exact sciences – so in musical terms, there is no end to this, it’s an endless debate. What will you define? If something is bad? If it’s good?”

Tiago Pereira was Tiago Pereira’s first target audience. “The MPGDP served to dismantle all of my prejudices. Prejudice is ignorance. As you get to know things you say, ‘Ah, I didn’t know!’ This is the story of my life, from the beginning. Now I still have many prejudices but, pffff, I don’t know, I’m 70 times less prejudiced than when I started, and it was because of deep ignorance.”

If you spoke with the version of you from 15 years ago, what would you say to him? “He was an asshole, an idiot who knew nothing about anything. This is the problem for a lot of people: having prejudices about things, when we have no idea what they are. It’s a question of education. At school you’re not taught to ask questions, you’re not accustomed to being curious, and so you’re not curious all your life. Either you’re curious by nature, and you’ll instigate it, or you’ll never ask the ‘whys.’ There’s a film in which I interview Bitocas, a musician who invents a lot of things, and has a lot of history that revolves around this issue of the tradition of things. His mother baked a cake in two pans, and he went to ask her, ‘why do you bake the cake in two pans?’ She replied, ‘because my grandmother baked the cake in two pans,’ and so he asked his grandmother. When he got to his grandmother, she said to him, ‘Since I didn’t have a big pan, I made it in two pans.’ The shame of asking why perpetuates hollow traditions and bacocas, but fortunately Tiago – a.k.a. Little Old Lady Pereira – doesn’t have porridge at the bottom of his questions, and goes to the bottom of things, like someone going to the bottom of a pot. “Against the taboo, record, record!” could be his battle cry, and before this struggle for self-esteem there could be quaije-nadica to add. Just that classic saying of Miranda do Douro: que nos faga bum porbeito.

Tiago Pereira is the son of a musician, grandson of a matriarch of Beira Baixa, and father of A Música Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (MPGDP), a collection of films of “music and choreography from various genres.” (Translated to English, it means roughly “Portuguese music liking itself,” or “Portuguese Music with a Taste for Itself.”) More than being about music or tradition, MPGDP is about the self-esteem of each person, the memory of all people, and the desire to level the attention. Tiago doesn’t have a driver’s license or paid holidays. He says he doesn’t like fast cars and he gets bored when he’s not working: he suffers from a messianic urgency in what he does – that is, the registration of an oral tradition that will disappear within a few years.

The director ignores the taboos of the foolish and the lame, recording frenetically, without stopping to judge – from Miranda do Douro to Ilha das Flores, placing beloved Portuguese singer-songwriter Conan Osíris on the same level as a series of old ladies and gentlemen who sing to keep themselves company. Countless times, they have already pegged him as the Michel Giacometti of the 21st century, in a comparison with the author responsible for the biggest ethnomusicological collection in Portugal – but this little nickname was exorcised in 2015, in a film by the title “Why I Am Not the Giacometti of the 21st Century.” What can I call him, then? Tiago prefers to introduce himself as “a director who films little old ladies.”

"I’m an activist of collective memory, but I just say that I film little old ladies."

"I record people’s knowledge. I don’t record because it’s traditional, or because it’s no longer traditional."

"We live closer to the Black blues than to the lady who sings in the garden behind our house."

"When people don’t have things planned, they stay, and lose track of time."

"You were there because, yes, you gave time to time. You had time, period."

"Each person, in his or her time, has his or her importance, because each person exists according to the time where he or she is."

"Tradition has always been contemporary. If not, we would be in ancient Rome, using togas and sandals."

"Doing things slowly is sometimes a practice, more than a time in itself."

It’s true that Tiago’s work is focused on music and memory, but if we pay attention, that’s not usually where he points his camera. Our conversation opens with a tight close-up shot, in autofocus mode. “How did you start working with self-esteem?” is what we asked. “From the moment you leave the cities and the highways, and start getting lost in the villages, the first thing you understand is that people think they have nothing to give. You talk about the songs, and they always tell you ‘but I know nothing.’ What does that mean? What does it mean, ‘I don’t know anything good?’ And then I realized that it has everything to do with parameters. Obviously, people have their televisions at home, and they get a lot of their definition of parameters for singing. More and more, you only sing in controlled places, and then people get the idea that to really sing you have to have high heels and makeup and always sing in tune, and have a jury that will evaluate you, because that’s what they see in the shows.”

Does Tiago’s interest in singing, chatting, and aphorisms that people know by heart have this effect of raising self-esteem? “It’s not just interest. What happens is more curious than that. I’d say, ‘Get outta here: I’m more interested in your singing than I am in the television.’ And when I recorded it, I’d put it on the internet right away, and people would start watching it. And these people that they saw were nearby. So there was a kind of local virus, which is to make something viral in just one place. This local virus raises self-esteem and literally increases people’s cognitive abilities. After a day or two, sometimes a week, they’d call me or send a message saying, ‘Come back, I’ve just remembered more!’ – that is, self-esteem also has to do with the cognitive abilities that reinforce everything that really counts. And so, the ladies remember many things…”

MPGDP is such a basic project that it was only a matter of time before it began to diversify, giving rise to La Música Ibérica Queriéndose a Sí Misma (Iberian Music Liking Itself), A Dança Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (Portuguese Dance Liking Itself) and Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (Esporão & Portuguese Cuisine Liking Itself). We asked Tiago if the main objective of this last project was to take gastronomical traditions out of the shadows, and the answer escaped from the parameters of the traditional. “It’s not about traditions, because these days ‘tradition’ is a very complicated word, just like the clichés: heritage, identity, authenticity. There are easy words and difficult words to describe things. Both for Esporão and for MPGDP, I record people, and I record what people know. With the food, I recorded the recipes that people knew about.”

Those who peruse the episodes (22 so far) will discover all kinds of recipes: some passed from great-grandparents to grandparents and from parents to children, others not so much. “There’s a video that I like very much, with two ladies in Évora talking about soup from Beldroegas. One said, ‘Ah, but I don’t put in potatoes,’ and the other said, ‘No no no, I put in potatoes!’ I record people’s knowledge, I don’t record it because it’s traditional or because it’s no longer traditional.”

Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria started in late 2015 with the co-authorship of Chef André Magalhães. Between the cataplana of Litão and Algas, and the caldeirada of Fragateira, there is a series of geographies, regional ingredients, and the sharing of knowledge – from well-known chefs as well as from unknown cooks – always as a sort of voyage of flavors. What dish or snack is indelibly engraved upon the director’s memory? “There’s a soup that my grandmother made, which I’ve been looking for ever since. It was called Santa Teresa soup. It had potatoes, tomatoes and boiled egg. I never saw it again. Sometimes I ask if anyone knows about the soup, but… nothing. I couldn’t find it. I looked once at Maria de Lourdes Modesto, but it had another name and it wasn’t exactly as my grandmother made it.”

We wanted to know if cities kill the roots of things. “I think they create other roots. They don’t kill, they transform. It has to do with times and with cycles, with migrations, and with a certain poverty that was experienced at a certain time in the country in the 20th century. Many people came to Lisbon and forgot their roots, because of the stigma of shame. There is something that gets lost, a certain popular wisdom that you don’t find in university. It’s not the opposite, it’s just another wisdom. You see this shame when you ask where people are from and they don’t tell you the name of the village, they always name the closest city. If you ask someone from Abraveses, they won’t say they’re from Abraveses, but from Viseu. First because people think that no one knows, and then also because of the stigma.”

Tiago remembers a dialogue he heard in Porto, involving wagons, donkeys and two interlocutors. “One of them got angry and said, ‘I don’t agree with anything, none of that.’” (For “none of that” he used the term “nadica,” a very particular old slang of complete negation, something like the English “less than zero” – but stronger, and more colloquial). “Obviously he was from Miranda do Douro and wanted to show that he was proud to say ‘nadica.’ He explained that having a donkey and a cart was as expensive as having a car in Lisbon, that people had to understand how much a donkey and cart cost and that it was not synonymous with poverty.”

Would this shame about that which is rural, or foolish, be linked to the shame of singing in Portuguese? “Of course – it dominated everything. It was a shame of poverty. It was like poverty was something cursed, and you couldn’t show that you were poor, so you got into that logic of the nouveau riche. That’s why you have these emigrants’ houses: you have to show that you’ve been successful in life, that you’ve managed to completely counteract the stigma to which you were somehow condemned. But then there are also other people who came to Lisbon and created roots in Lisbon, with fragments of many other cultures. These are the so-called urban roots, a mixture of everything and something else that you cannot define. There’s an episode at Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa with chef Hugo Brito, and a pork-hearts recipe from Alfredo Saramago’s book Cozinha de Lisboa e Seu Termo, which is a lot of that – it’s the only episode with a completely Lisbon dish, which is exactly what it’s all about. It doesn’t restrict, it doesn’t define the question of what’s traditional, or where it comes from. It opens everything. The heart is studded with cloves, and the cloves came from I-don’t-know-where before they ended up here, and so it’s already a recipe from Lisbon that’s open to all the cultures that are here these days.”

It seems to us that the existence of MPGDP since 2011 has contributed to more people losing their shame of singing and hearing songs in Portuguese. “Nowadays, there’s a lot of information available. You have internet, radio, and television, and much easier access to things. For a long time, you received whatever came to you, and the culture that reigned was Anglo-Saxon. If you were 14 years old with a garage band, you weren’t gonna sing in Portuguese. Usually what you see from new pop or rock groups are imitations of what they like, and then they start to transform. And often, fortunately, they turn into something else and leave the starting point behind. It’s often said – and I’ve said it for a long time – that especially in the big cities in Portugal, we live closer to the Blacks who sang the blues than to the lady who sings in the garden behind our house, or our own grandmother.”

In the context of a bossa nova song, Vinicius de Moraes wrote for so many people to sing: “I’ve danced the twist too much / But I don’t know / I got tired / From calypso to cha cha / I only dance samba / I only dance samba, vai, vai, vai, vai vai…” “We’ve always been closer to this culture because it was this culture that everyone cared about. Then what happened was a discovery of metrics. Which is a bit stupid, because if you notice, you have popular poets who have always composed in tenths, without reading or writing, and who have turned the metrics around even in the logic of tongue twisters. They say very quickly, ‘já disse à mãe do cário que mandasse o carário embora, é cário, é carário, é cário, nós não queremos mais carários agora.’” (Tiago repeats a traditional Portuguese tongue-twister, something with a function comparable to “I wish to wish the wish you wish to wish, but if you wish the wish the witch wishes, I won’t wish the wish you wish to wish.”) “The rhythm of this is very difficult and the old ladies have always used it, but you didn’t see Portuguese singers or musicians picking it up, simply because they didn’t have the knowledge. Even knowing that, Giacometti opened a whole new logic: it was at that time, and for the people of that time. Access to popular music has always been difficult and this is one of the big issues that MPGDP came to resolve: making it easy for the old lady to access Portuguese musical culture, because you can go there and find everything. Before you had some things by Ernesto Faria de Oliveira on the internet, from the University of Minho, which Domingos Morais had put out – but very few people knew about it. Giacometti was very difficult to find, because the full edition of Público by José Moças hadn’t been released yet. There were some videos circulating, almost a kind of pirate radio, with the time codes on top. His audios didn’t exist… Armando Leça was only released in the Alentejo very recently: I don’t know where it had been since 1939! What was Portuguese was always this thing about the miserable condition, the poor little Portuguese who doesn’t invent anything and doesn’t do anything right. There was a lot of that. From the moment you opened the library, you were able to discover other things. [The band] Diabo na Cruz are very important in this sense. When Jorge Cruz starts to make music and records from his library, a whole culture begins to reach other people who probably only ever heard rock music sung in English.” And that’s how Portuguese rock emerges. “I think that from the moment that you have the publishing houses Amor Fúria and Flor Caveira, in the first decade of the 21st century, you have [the band] B Fachada, you have all of that – it has opened up a lot, to the point where we are today, where it’s possible to sing in Portuguese without fear.”

And did the same thing happen in the field of gastronomy? “There was also a denial of traditional products. It had to be a Fausto Airoldi pulling up the sardines, not a Portuguese. When he arrived here, he began to make fine-dining dishes with Portuguese ingredients, and only then did the chefs all start talking about Portuguese products, and you even have that incredible phrase from Alexandre Silva do Loco, which says, ‘For me, Portuguese cuisine is not Alentejo pork with Vietnamese clams and Spanish pork.’ I think that’s what’s pertinent. Like when you play and play the same song many times over – they are actually two very different paths.” Born in Mozambique, Fausto Airoldi spent 30 years in Portugal before leaving for Macau; all of these are destinations with menus written in Portuguese. We’ve already heard of the quest for the long-lost soup, but what about his favorite restaurants? What were the most striking, after so many roads and so many places to film? “Road food is a very complicated thing. Most restaurants outside of Lisbon and Porto have the problem of diversity. Either you have restaurants that are clearly regional, or you’re still stuck with the issue of always having the same steak, the same octopus, the same bacalhau à lagareiro, the rojões à minhota – those meals that they always have – and you don’t move on from there. In addition to always being the same dishes, they’re always the same everywhere, whether you’re in São Pedro do Sul, Fafe or Chaves. In the Alentejo it’s different: you have a lot of regional food and those ex-libris dishes – the sopa de cação, the segredos de porco preto…” But here, two fondly-remembered tascas surge into the conversation – both of them regional, of course. “I remember that I went to Serra da Aboboreira, just near Baião and Amarante, and there was a Tasquinha do Fumo. It was an incredible tasca like that Tasca do Petrol, in Monchique, which is also incredible – they’re two tascas where you eat and you’re like, pffffffff! Sometimes I don’t even remember the names.”

And has the work of chefs and culinary festivals reduced the distance between the product and the plate, between the market and the country? “Yes, of course, but – as hard as it is to hear – that’s only for an elite because it doesn’t reach most people. It exists for those who have money. In Episode 16 of Esporão & A Comida Portuguesa a Gostar Dela Própria, the chef of Feitoria, João Rodrigues, cooks black pork with green cabbage – in this case, a D.O.C. cabbage because Sr. Domingos (a.k.a. “Mr. Trigger”) comments on why his cabbages, planted in Reguengos de Monsaraz, are different from the others. We quote from the video: ‘the most important thing is for us to know what we are going to eat. If they serve us lettuce, we need to know how it was treated. Sometimes I go to sell at the market and there are people who even say, “over there the guy sells cheaper, I don’t know how much,” and I ask, “and this plant comes from where?” and they say, “don’t know.” But this is what’s important. We’re here, we sow the seeds, we know what we plant and harvest. It puts a big responsibility upon me, to fulfill. I’m not going to do anything else. I’ve been selling in the market since I was 14 years old, I’m now 84… It’s been a few years.” João Rodrigues’s dish pays tribute to one of the most symbolic festivals in Portuguese society – the slaughter of the pigs – and justifies: “people are increasingly distant from their origins and face life in an intense way, with much more speed, very automatically. They have little time to stop. These days, time is almost a luxury – or the greatest luxury of our society.”

Turning back to the man behind the lens: “Often the average consumer doesn’t know where the product comes from. Maybe people should ask more questions. In a restaurant, I don’t know where that octopus, that steak, those pork cheeks come from. It’s still very much a chef thing, but for the people to have that concern, they also need to be at another level which allows them to be sufficiently relaxed to have that concern on an economic level.” And it’s at this moment that we understand: Tiago invented for himself a job that forces him to constantly return to his origins. “It was unintentional. It’s like the Greek myths. When you run away from your destiny, it’s fulfilled. I record traditional music, my father played traditional music… it’s obvious that I’m always returning to my origins. I grew up with my grandmother in Estreito, in Oleiros. My grandmother, her sisters and cousins… the women did everything, took care of their children, protected their husbands, went to the gardens, took care of the animals… They made the pork sausages. The man just put the knife in the pig and then drank with his friends, and then it was the women who would prepare the meat, grill, fry and make the soups. The women always had time to take care of their grandchildren. It wasn’t easy. I managed to get a job that constantly reminds me of this issue, of women. And I still see this – that the actions that have to do with food and caring are done by women. I lived with my grandmother until I was nine years old, but since I was little and until I was 12, I spent three months of every summer in her village. So I have many memories of the village that persist in what I do.”

Unfortunately, the grandson has no memory of his grandmother singing or playing. “I remember my father once going to my grandmother’s house with an adufe, and he left it somewhere. When we went back to get it, she had the adufe in her hand as if she had known how to play it her entire life. But she didn’t play. The truth is that no one would just have a grip like that on an adufe, if they didn’t know how to play it. Things really change a lot, because in Beira Baixa there was a lot of adufe playing. We are witnessing the decline of things. This generation has never experienced the peak and that’s a little sad for me, for what I do.”

In Tiago’s living room, with traditional masks and clay pieces, we can see the poster for the film “Why I Am Not the Giacometti if the 21st Century,” among other pieces – and another, announcing the first musical picnic of MPGDP. “The first was mythical. I don’t think anyone will forget it for a long time. It was in Monforte da Beira. MPGDP had to have a birthday, and I didn’t want a banal party with stage and musicians. Because in November I had been filming in Monforte da Beira and I got along well with the president of the Junta da Freguesia, I told her, ‘Look, I’d like to have a picnic. I have no idea how this is going to happen. I tell people to come, everyone brings their own meal and whatever they want to play, and that’s it.’ After that, it was crazy. Two choirs from Serpa came, two choirs from Viana do Alentejo, a group of drums from Marinha Grande, a group of drums from Alcochete, two groups of women from Minho who sing, people with bagpipes, even Jorge Cruz from Diabo na Cruz… It was suddenly this madness of 600 people singing and dancing, spontaneously, just because they wanted to.” There were many people who took twice as much time to get to the picnic as they were able to be at the picnic. They tried to replicate the spirit of that first picnic for subsequent ones, “but last time we had bad luck because it was raining and we had to go to a pavilion in Viana do Castelo. The last time it was at the Jardim da Estrela and so there were too many exit points, people didn’t stay, because they’d go eat I-don’t-know-where, and disappeared for I don’t know how many hours… When people don’t have things planned, they stay and lose track of time. Nowadays everybody has everything programmed and [at the picnic] there was no plan for anything. A funny thing was the lady from the parish council saying, ‘Ah, I have the SPA here asking what songs we’re going to play,’ but we couldn’t program anything, people would just play whatever they wanted to at the moment. You have this idea of having everything scheduled, you’ll eat at this time and then you’ll do that, and announce it all at the Facebook event that day… But there was nothing planned, nobody knew what was going to happen. You’d come in, eat when you felt like it, and if someone played you could play along, or not. You were there because, yes, you gave time to time. You had time, that’s all. The fertile period was between 13:00 and 17:00, four intense hours.”

And how do you deal with this title of Giacometti of the 21st century? With irony? “It has been worse – I’ve never liked it very much. There’s a time when you realize that each person has their own importance in their time, and that’s a bit of it. Armando Leça has his importance in his time, like Artur Santos, like Giacometti – because it’s a bit impossible to compare people because everything happens in different times. Armando Leça didn’t have electricity. He couldn’t go to the villages. He had a tape recorder that needed to hook up to power, and he had to call the people to come by public transport to the nearest town where there was electricity because most of them didn’t have it. Then Giacometti and Nagra couldn’t go everywhere either. They had a battery-powered, super heavy-duty coil recorder. Nowadays we go with a little tape recorder and a camcorder, we record it, and soon afterward we put it on the internet. Once I recorded Zeca Medeiros in the Azores in the morning. He was going to Faial that day, and by the time he landed, he already had 400 ‘likes’ on the video. And he was like, ‘but what happened? What…?’ Each person, in his time, has his importance, because each person exists within the time where he is. I do that in my time, in the digital age.”

So how does the director and mentor of MPGDP, the “collective memory activist,” introduce himself professionally? “I’m a collective memory activist, but I say that I film little old ladies.” And what does the director of little old ladies and cooks do when he is not working? “I work. I can’t [stop], I get bored. I have to do things. I stop when I’m tired. This is a process of rest that is something else, but for a long time when I stopped I was always aware that someone was dying and I was not filming.” The director comes from a lineage of documentary filmmakers dedicated to recording the oral tradition of people who worked in the fields in the 1930s and 1940s, which is disappearing. “Nowadays, professional actors and singers are the ones who memorize things; other people don’t need them. There’s got to be another tradition which has to do with the digital age, and which will be completely different. Today, no one memorizes 200 songs by heart, because they can find everything on their cell phones. But the little old ladies in the villages can recite 200 poems by memory, without knowing how to read or write. When you meet people who keep the oral tradition alive, obviously you record them… So, when I have time, I also have the notion that this work is urgent, because these people are going to die. We’re talking about 2030 – it’s one more decade.”

So the collection process starts with the elders? “I record the elders, just like I record the youngest. I record the younger ones who have learned from the older ones and who make a point of knowing songs by heart. This story of cante alentejano being Intangible Heritage of Humanity helps to draw in younger people. There are six year olds, ten year olds who sing and do choral groups, and who know these ways. Many of them invent fashions, which is great, because if you do, you know it by heart. It’s all a process of recording what’s disappearing.”

Much of the material that generations of Portuguese learned in school – at least those Portuguese who were born in the first half of the twentieth century – was based upon words and mnemonics. They learned didactic songs and the names of mountains, rivers, and tributaries. Or the main stations of the trans-Siberian railway line that some septuagenarians still have at the tips of their tongues: Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, and Vladivostok. “It comes a lot from Giordano Bruno of the Renaissance, who already had this question of the theater of memory – which, from then on, establishes connections between colors, positions, sites, images, geographies – to remember things. And old people have many tips for remembering things by association. There’s a man I recorded who said, ‘Port wine gives a lot of memory, and has a lot of science.’ Everything that is truly spontaneous has a lot to do with having the right mnemonics, to remember easily what rhymes with what. When they’re under the influence of wine they become looser, and then it’s easier: as they have these mnemonics, they free themselves. They invent I-don’t-know-what and pow, it just sounds right. They are the precursors of hip-hop. This gentleman who was a closeted poet all his life, would come to you and say, ‘look, you want a poem – on what foundation?’” (A foundation is like a motto or a theme, and the poet always gives it a twist.) “You might say, ‘I want one on death,’ and he recites one on death in front of you. ‘I want one on that yellow house,’ and he makes up one on the yellow house.”

Is it also about giving new style to old songs, with the help of contemporary musicians? “Tradition has always been contemporary. If not, we would all be in ancient Rome, using togas and sandals. Everyone has the importance that they have in their own time, and all of this just accompanies time. The tradition that stagnates ends up dying. For example, the caretos of the Ousilhão always had tradition: it’s an initiation rite for boys in the village of Ousilhão, but at a certain point there were no more males being born, so if the women didn’t take on the costume and the caretos, there was no one to do it – they didn’t go into the street, and the tradition died. So they had to accept the transformation of the tradition. In a way, I don’t look for costumes at all. What I seek with my work is to level out the attention. I think that we live in a world obsessed with the attention peaks of television, etc. and that the means of communication do not give importance to all things. Music doesn’t have hierarchies, so I want to give importance to the musician in the philharmonic, as much as to the little old lady who sings alone, or to B Fachada, to Jorge Cruz or to Márcia. That’s why I record everything from Conan Osíris to the little old ladies: because I want people to look at them.”

So your Machiavellian and megalomaniac goal involves recording the millions of Portuguese who sing alone, little old ladies first? “Yes, always recording, because what I’m looking for in MPGDP – and in a way also with gastronomy – is the primordial meaning of things. I want to record the old lady who is cooking and singing to herself. It’s singing in a primordial sense, because everyone has always sung. Nowadays it’s stigmatized: if you sing alone in the street you’re drunk, or crazy. Many years ago, people sang to keep themselves company. They sang just because. Only later did society begin to turn this around. We no longer sing just because. What’s important is to make people sing just because, to sing outside of the controlled environments. That’s what I want to level out: this need to sing.”

And a culinary example emerges: “I remember an incredible video of Esporão with a lady cutting a cucumber just for herself, making a gazpacho that’s just cucumber, water, garlic and a tiny bit of olive oil. But the way she cuts the cucumber without even looking is impressive. In the end, it’s perfectly pulverized. It’s a bit in that sense – you’re always looking for what comes from the origin, whether it’s cooking, singing or dancing.”

What do you think is the memory of a people? Is it very private? “First, we have to define what is ‘a people.’ For me, it’s always in the anthropological sense – it’s individuals. I record the memory of people, so it is more private. It has a lot to do with knowing how to listen to people – nowadays almost nobody knows how to listen. It’s curious that in Lisbon you have the expression, ‘look here’ – but you arrive in the Alentejo and they say, ‘listen up.’ We’re so accustomed to looking, and so little accustomed to listening. I listen to many people. I give them that space where they can be whatever they want. Then I’m there, and I receive, often only after having listened to them for an hour, telling about their illnesses or their misfortunes.”

“We’re talking about ‘going slowly’ here, but sometimes you have to know how to do things slowly in little time. Doing it slowly is sometimes a practice, more than a time in itself. Sometimes you have little time and you can still do it slowly – I do that. I remember Júlio Pereira Pires, an impressive man who has already died. The first time I recorded with him, I took someone from the library in Vila Velha de Ródão who wanted to consult with him, because he could ward off the evil eye. It took him an hour to do the evil-eye, to tell the story of his wife’s illness. This happens all the time, but I never stop the camera.” Tiago is therefore a confidante, a psychologist, and sometimes a borrowed son or grandson. “There’s a very strong social side to MPGDP, which has to do with this exchange. I go there, they give me this, then I distribute what they gave me. They always ask me, ‘Where are you taking me?’ and I say, ‘To the world’ and sometimes the world gives back to them. This process of discovering things in them that they didn’t know they had, is also very important.”

How often do we survive thanks to the generosity of strangers, right? “People are always generous. The happiest man I’ve ever seen in my life lives in Chamarritas, on the island of Pico. He was always completely overjoyed and only said, ‘Guys, let’s go celebrate!’ I recorded with him, and in the end, someone told me that his wife was dying at home. And she died the next day. Sometimes you need to look at yourself in the mirror and ask who you are to deserve such generosity. Who do people stop doing their things, to go and sing for you? Why? Why should it be so?”

Does Tiago have any strategy for living more slowly? Or to avoid being sucked into the nets that steal our attention? “I’m super fast and I hate technology. I don’t have strategies. I really like to walk in order to think. It’s one of those things that I do slowly. I don’t have a driver’s license and I don’t like to travel fast in cars. As for technology, it’s more and more of an economic process rather than a help to life: it makes you a slave dependent upon upgrades and new models, so I try to get away from it.”

Without a driver’s license, it would be impossible for you to do your own projects alone. “Even with a driver’s license it would be impossible. It could never be a solitary job. You always need someone. It’s important to have people with you who haven’t mastered the kinds of things that you record, to allow you to have a certain amount of mental sanity, and not to think that sometimes you’re dreaming – that it’s actually happening. I record people, mostly at the limit of their abilities, and then there are always things that impress you. It’s like Dona Rosário of the Algarve, who’s 103 years old, and plays the concertina. I recorded her when she was 99, and it was really powerful. Her daughter said that Dona Rosário woke up in the middle of the night and played the concertina alone. A 103-year-old lady addicted to concertina? Sometimes you need to pinch yourself, to prove to other people that you’re not crazy, that something like this really does have an unassailable human force – otherwise you’ll get used to living in a bubble and you think it’s all like that.”

How do you teach someone not to find something lame? “Discussing taste. People these days are always discussing what is good or bad. This doesn’t make sense, in terms of music. For example, the whole controversy with Conan Osiris: ‘That’s horrible, that’s bad, he sings badly…’ We have to be great musicians, to know everything about frequencies, about all notes, to have absolutely distinguished ears to be able to define whether he sings well or badly. We don’t know, though – these parameters don’t exist to actually define who sings well. To understand why we like him or why we don’t, we have to disassemble taste. How did you grow up? Where did you grow up? Who did you run with? What did you hear? With whom did you listen? What did you eat? And then you start to understand and disassemble what made you like certain things, and maybe you’ll be more open to enjoying other things, and understanding other things. The only thing we can really discuss is taste. Everything else, you can’t. It’s silly to say that taste is not to be discussed. No – you can only discuss taste. The rest you can’t discuss because it’s too concrete to discuss. There are things that are exact sciences – so in musical terms, there is no end to this, it’s an endless debate. What will you define? If something is bad? If it’s good?”

Tiago Pereira was Tiago Pereira’s first target audience. “The MPGDP served to dismantle all of my prejudices. Prejudice is ignorance. As you get to know things you say, ‘Ah, I didn’t know!’ This is the story of my life, from the beginning. Now I still have many prejudices but, pffff, I don’t know, I’m 70 times less prejudiced than when I started, and it was because of deep ignorance.”

If you spoke with the version of you from 15 years ago, what would you say to him? “He was an asshole, an idiot who knew nothing about anything. This is the problem for a lot of people: having prejudices about things, when we have no idea what they are. It’s a question of education. At school you’re not taught to ask questions, you’re not accustomed to being curious, and so you’re not curious all your life. Either you’re curious by nature, and you’ll instigate it, or you’ll never ask the ‘whys.’ There’s a film in which I interview Bitocas, a musician who invents a lot of things, and has a lot of history that revolves around this issue of the tradition of things. His mother baked a cake in two pans, and he went to ask her, ‘why do you bake the cake in two pans?’ She replied, ‘because my grandmother baked the cake in two pans,’ and so he asked his grandmother. When he got to his grandmother, she said to him, ‘Since I didn’t have a big pan, I made it in two pans.’ The shame of asking why perpetuates hollow traditions and bacocas, but fortunately Tiago – a.k.a. Little Old Lady Pereira – doesn’t have porridge at the bottom of his questions, and goes to the bottom of things, like someone going to the bottom of a pot. “Against the taboo, record, record!” could be his battle cry, and before this struggle for self-esteem there could be quaije-nadica to add. Just that classic saying of Miranda do Douro: que nos faga bum porbeito.

TiagoPereira

Memory on the tip of the tongue

Interviewed on 2 July 2019 at Tiago’s home in Lisbon

Tiago Pereira is the son of a musician, grandson of a matriarch of Beira Baixa, and father of A Música Portuguesa a Gostar dela Própria (MPGDP), a collection of films of “music and choreography from various genres.” (Translated to English, it means roughly “Portuguese music liking itself,” or “Portuguese Music with a Taste for Itself.”) More than being about music or tradition, MPGDP is about the self-esteem of each person, the memory of all people, and the desire to level the attention. Tiago doesn’t have a driver’s license or paid holidays. He says he doesn’t like fast cars and he gets bored when he’s not working: he suffers from a messianic urgency in what he does – that is, the registration of an oral tradition that will disappear within a few years.

The director ignores the taboos of the foolish and the lame, recording frenetically, without stopping to judge – from Miranda do Douro to Ilha das Flores, placing beloved Portuguese singer-songwriter Conan Osíris on the same level as a series of old ladies and gentlemen who sing to keep themselves company. Countless times, they have already pegged him as the Michel Giacometti of the 21st century, in a comparison with the author responsible for the biggest ethnomusicological collection in Portugal – but this little nickname was exorcised in 2015, in a film by the title “Why I Am Not the Giacometti of the 21st Century.” What can I call him, then? Tiago prefers to introduce himself as “a director who films little old ladies.”

"I’m an activist of collective memory, but I just say that I film little old ladies."

"I record people’s knowledge. I don’t record because it’s traditional, or because it’s no longer traditional."

"We live closer to the Black blues than to the lady who sings in the garden behind our house."

"When people don’t have things planned, they stay, and lose track of time."

"You were there because, yes, you gave time to time. You had time, period."

"Each person, in his or her time, has his or her importance, because each person exists according to the time where he or she is."

"Tradition has always been contemporary. If not, we would be in ancient Rome, using togas and sandals."

"Doing things slowly is sometimes a practice, more than a time in itself."

It’s true that Tiago’s work is focused on music and memory, but if we pay attention, that’s not usually where he points his camera. Our conversation opens with a tight close-up shot, in autofocus mode. “How did you start working with self-esteem?” is what we asked. “From the moment you leave the cities and the highways, and start getting lost in the villages, the first thing you understand is that people think they have nothing to give. You talk about the songs, and they always tell you ‘but I know nothing.’ What does that mean? What does it mean, ‘I don’t know anything good?’ And then I realized that it has everything to do with parameters. Obviously, people have their televisions at home, and they get a lot of their definition of parameters for singing. More and more, you only sing in controlled places, and then people get the idea that to really sing you have to have high heels and makeup and always sing in tune, and have a jury that will evaluate you, because that’s what they see in the shows.”

Does Tiago’s interest in singing, chatting, and aphorisms that people know by heart have this effect of raising self-esteem? “It’s not just interest. What happens is more curious than that. I’d say, ‘Get outta here: I’m more interested in your singing than I am in the television.’ And when I recorded it, I’d put it on the internet right away, and people would start watching it. And these people that they saw were nearby. So there was a kind of local virus, which is to make something viral in just one place. This local virus raises self-esteem and literally increases people’s cognitive abilities. After a day or two, sometimes a week, they’d call me or send a message saying, ‘Come back, I’ve just remembered more!’ – that is, self-esteem also has to do with the cognitive abilities that reinforce everything that really counts. And so, the ladies remember many things…”