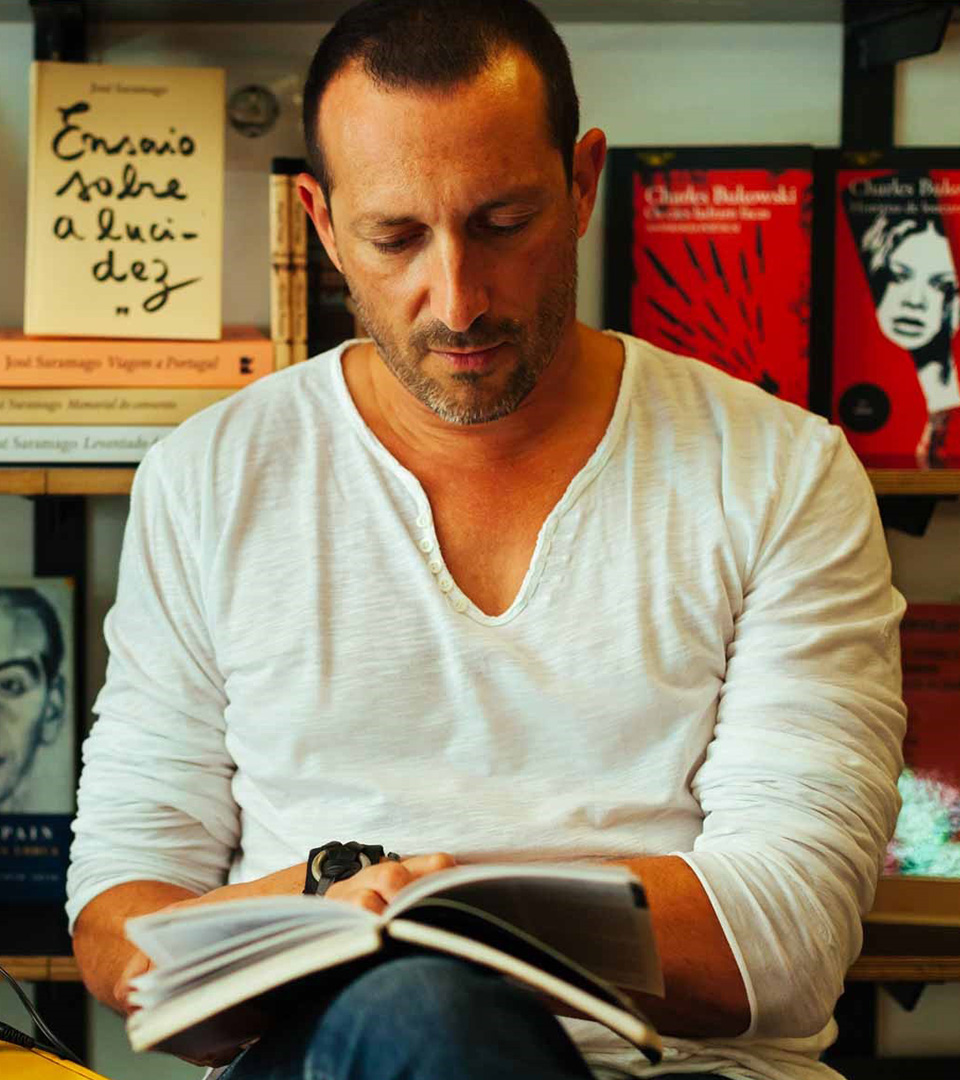

RicardoLopes

Interviewed in the Menina e Moça Bar, in Lisbon.

Listening without headphones

Ricardo Lopes did not live in the 1960s, doesn’t have hair that goes past his shoulders, never mentioned names like Janis Joplin or Jimi Hendrix, and never launched the phrase “peace and love,” but nonetheless, during the hour and twenty-four minutes that we spent together in the Menina e Moça bookshop, he referred countless times – passionately – to the importance of the mutual support that he finds in their communities, as if he were a hippie at heart.

“Connection, and not a digital one, is something that we have to value more.”

The son of candy and pastry manufacturers from the Leiria region, from an early age he would have learned the best recipes for combining people, music, contexts, and brands – even if he hadn’t later studied and worked in marketing and advertising. There are those who call him an organizer of cultural events, a musical curator, or one of the two heads behind the Lisbon Living Room Sessions, but he is no longer an ad-man. His rhythm is different now, with more time, more longevity, and more finger-snapping.

"The absence of hurry makes projects more solid."

"Nothing is done, nothing is consolidated, in a hurry."

"You have to live, you have to listen… You don’t become a genius from one day to the next."

"It’s important to turn off for a few moments, to allow you to be with yourself."

"We’re the right country, at the right time, with the right tendency. Portugal can teach the rest of the world to slow down."

"How much time do we really give ourselves to others?"

"We can’t keep going continuously in this frenzy of wanting everything, but being nothing."

We met at the Menina e Moça bookshop, on the vibrant pink street of Cais do Sodré, in Lisbon. Curiously, it was in this space – while its name was still Velha Senhora – that the project Ricardo has been working on for more than four years began. That night, frustrated by the noise of an office Christmas dinner, Ricardo and Joanna Hecker (also a Slow Forward ambassador) agreed to experiment with a project that creates space for listening to music in an intimate way – and without Secret Santas. The first Lisbon Living Room Session happened the following month, on January 25, 2015, with Diego el Gavi and his band – the very same musicians that Joanna and Ricardo could barely hear in Velha Senhora.

Let’s go back to Leiria, to the time when the Hidromel Factory – and the confectionery of the same name – distributed sweets throughout the country and employed about 200 people. “The factory was 7 kilometers from Leiria, in my mother’s hometown of Soutocico, which means a group of little chestnut trees.” Ricardo’s parents became important people in the region, and not only because of what they produced: “When you have a company with 200 employees, not only do you have relevance in economic terms, but also social terms.”

The factory was divided into several sectors. There were the candies, transversal across the entire year. But then, season by season, there was the canned fruit section, the candied fruits, the marmalades, the suckers, the Easter almonds, the cookies, and the “bolos-rei”, sold all over the place, and offered and personally delivered to the students of the prison school of Leiria on Christmas Eve. “I remember stealing peaches from the assembly line, already cut in half and pitted” rescued from a life in syrup. “During the holidays I used to use a forklift to load trucks. If you’re the boss’s son, you have to work. The house was in front of the factory and sometimes my friends were in the pool and I was working.”

Ricardo has never played any instrument. He has always been more in the production mode. “I remember a band of friends from high school who played heavy rock. Their band name was Ukurralle and they did a rehearsal, recorded it in the empty pool at my house. Birthday parties were always big and memorable. I think my route to production started there. It’s about knowing how to receive. How do you receive people at home? It was something I learned from my parents.”

In 1997, the year his father died, Ricardo went to Lisbon to study, and two years later he met “DJ Johnny, during one of those crazy Lux nights, that lasted until lunchtime the next day listening to vinyl at his house.”

Between the first and second squads of the CoolTrain Crew (a group of DJs and drum-and-bass musicians), Ricardo began to move around with a group that would become fundamental for new dance music in Portugal. “It was during the first generation – Johnny, Dinid, Tiago Miranda, MC Knowledje, Vítor Belanciano, Nuno Rosas, Rui Murka – and the beginning of the second generation, with João Barbosa (a.k.a. Lil’John a.k.a. Branko), Kalaf, Rui Pité (DJ Riot) and Alex Talhinhas, from Macacos do Chinês. Johnny plays an almost mentor-like role in our generation, someone with a deep knowledge of various musical genres who thought of the freshness of music as something timeless, but also as a cultural movement. He is a creator by nature.”

In 2003 Ricardo and Johnny launched the Leiria Jazz Sessions, “every Sunday for two years, taking jazz to downtown Leiria. The idea was to deconstruct the preconceived idea that jazz is all free jazz, with each musician playing for himself.”

The sessions showed Leirians how jazz influenced so many other genres (from hip hop to drum and bass, from soul to funk and bossa nova, from rock to reggae) or has common roots with music from Mali and the West African coast. “We took swing, standards, Latin American music project, afro-beat and new Portuguese authors. We tried to bring the best musicians of that generation – André Fernandes, Nelson Cascais, André Sousa Machado, Bruno Pedroso, David Biney, Craig Taborn, among so many others.” The space was the Camões Brewery, in the center of the city, with a 170-seat capacity. “When we went forward they thought we were crazy: ‘How are they going to bring jazz to a provincial city that may be financially and economically rich, but is very poor culturally, on a Sunday, at 21:30, when people are watching television?’”

At that time, on one of the Sundays of each month, Johnny would play vinyl, João Barbosa would create a set, and an invited guest would come along to recite poetry. Antonio Tabucchi was responsible for bridging the gap between jazz icons and Portuguese literature, the first being Miles Davis with Fernando Pessoa (spoken word by Kalaf), Duke Ellington with Natália Correia and Charlie Parker in dialogue with José Cardoso Pires. “The fear dissipated and we were always full.” There was a special episode with a couple of civil servants. “They came to me after a few months to thank me for the fact that this was happening in Leiria, and then they say, ‘We already bought two jazz albums.’ I got curious and asked what they were. Sarah Vaughan was the first. Okay, it’s commercial, swing, easy to hear – but good. The second was Thelonious Monk. I thought, ‘my work is done.’ In other words, a musician who is not easy to listen to – complex – this couple made it there. Just like I did, and still do my course, they can also do theirs. That’s the motive, the role as a musician or cultural agent.”

The great majority of his ongoing music projects take time to prepare, time to take root, time to grow – but in advertising, it’s all the opposite, all quick, all to be done by yesterday, and all to forget. “The absence of hurry makes projects more solid. Nothing is done, nothing is consolidated in urgency. We see constant ephemeral phenomena that are the best, the greatest, everything due tomorrow, everything with a great machine behind it, but the ones that have longevity are rare.”

What began in Leiria and then moved on to the Lisbon Jazz Sessions (at the Bicaense bar), the Lux Frágil Jazz Sessions, the Lisbon Living Room Sessions, and Fado Redux concerts, among other projects, was a growing path in adaptation to the environment and in the creation of small tribes of believers. “The habits help to create a sense of belonging and learning step by step, without being in a hurry. People know that the quality is there, that they can count on the moment today or next week or next month.”

In his musical projects Ricardo crosses several areas and creative heads, including musicians, DJs, writers, illustrators and photographers “to create a product, it has to make sense as a whole, people are waiting for references and anchors that can teach them something.”

It’s extremely important to know, “When you live in society and in a community, what is our role? Are we just here to receive, like consumers? Are we waiting for others to serve us, for the parish council or the town council or the government to take care of everything? Or can we also do something, at our own scale? And how can this have an impact on our community? That’s how all of the projects were born: with sharing, intervention, a certain slowness, but that really create a community.”

And the results in the community, are they palpable? “I feel recognition. One thing is the community of your street, your neighborhood, your city. Projects may be small, but they’re full houses. People are passionately there. With friends, passing the word. But there’s a gap between the people who do things with passion, where there’s not merely a financial aspect and the marketing approaches that don’t know what’s on the street or the journalists who don’t leave the newsroom.”

A lot of people are too busy to pay attention to the genesis of certain movements. “We live behind a screen, we walk down the street on headphones, we don’t have time for others, we don’t pay attention, we don’t get involved…”

What do you do to stop? “I travel. I disconnect completely.” And in Lisbon? “I don’t use headphones in the city, I try to listen to the rhythms of the city when I walk. I go out at night to listen to music, especially from Sunday to Thursday. Sometimes I go to places that nobody remembers, but there’s a musician I’ve never seen live, in a place that can be interesting – and this combination, on a Tuesday night… I’ve had so many unbelievable encounters that if I don’t try, don’t go, don’t get involved, they don’t happen.”

Ricardo obliges himself to explore unknown territories, almost like a mission: it is “a continuous curiosity,” which allows him to be his own novelty dealer, in 90% of cases. The idea is to understand if a band or musician can communicate with the public. “I remember Keziah Jones, a Nigerian musician, a reference in the Lisbon Living Room Sessions. When we were two years old, it was from that point on that we went beyond the underground of our friends.” Ricardo also remembers that the journalists woke up to the project because they thought, “‘How does a name like Keziah Jones play in a living room in Lisbon?’ There’s a very long delay, but you think, you’ve had this information for a long time, it didn’t have to be Keziah, it could have been António or Manel… Pay attention, have the experience, come and see.”

“I find him at the door of Bela, the tasca in the Rua dos Remédios where I go regularly to support other curators like Carlos Mil-Homens. And on a normal night of drinking, music, and friends, Keziah Jones appears with his hat on. I couldn’t remember his face and we started talking until somebody asked me who he was.”

Once Ricardo realized who he had in front of him, he didn’t waste any time in inviting him to the next L.L.R.S. session, and the musician accepted. “This happens when there are familiarity and trust, when they realize that people on the other side are real and do things with passion. Then relationships become intimate concerts, unique and unrepeatable, with news on Público and Expresso… Another thing Keziah said to me, which also has to do with time and authenticity, was that when he played a meter away from the audience, in a full living room, hot as hell, he thought: ‘here there are no tricks, you’re a street musician, either you know it or you don’t know it.’”

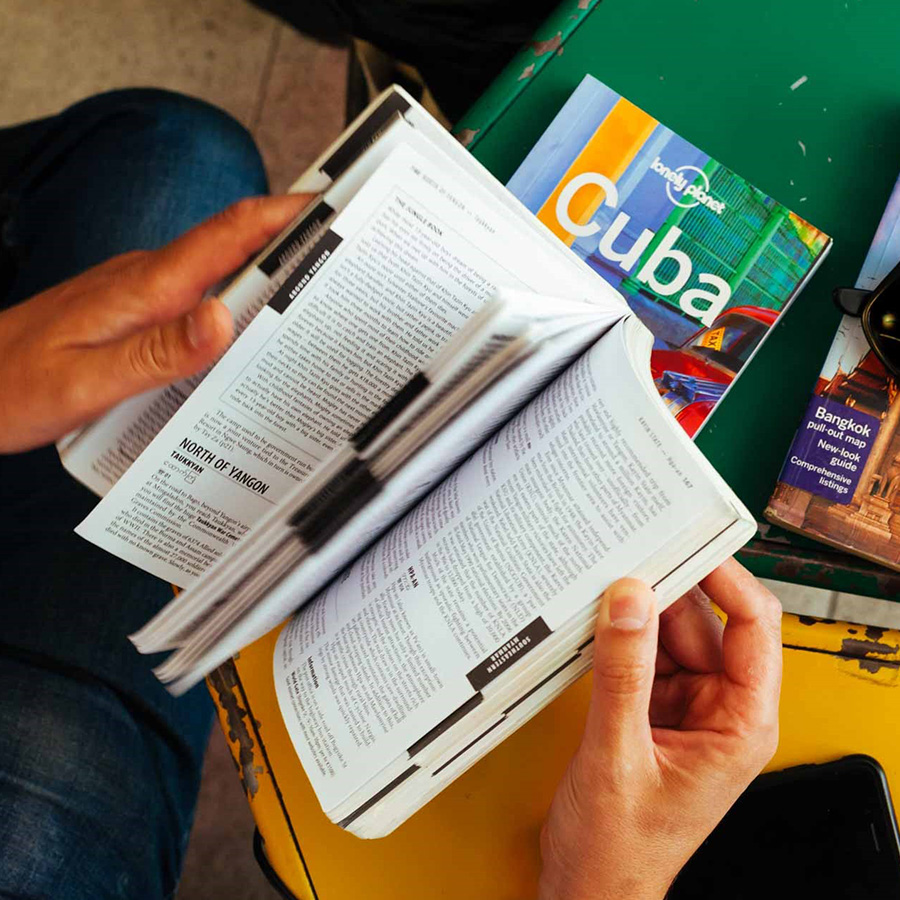

Intimacy, proximity, trust, and longevity are what Ricardo seeks in his projects, whether they are developed by two, four or more hands. In the midst of his work he travels, just as he did during the trip that was supposed to be three months – with only a one-way flight to Argentina – and ended up lasting two years. “It’s important to turn off a few moments to allow you to be with yourself.”

“Journeys like I do them, are unscheduled. I have a maxim, that is: When I start to get too comfortable *snaps fingers* I have to take off. I can’t put down roots. It’s about getting out of the comfort zone continuously.”

Which cultures can teach us the best ways to deal with time? “The countries that have marked me most are Buddhist cultures, a calmer culture that respects the time and space of each one. It can be seen in countries like Burma. I think it has to do with the delicacy of how they treat one another, but also with the fact that they are not so technologically advanced. They dedicate time to others, they want to get to know you, they’re willing to share, whether it’s a bed, a plate of food or a conversation.”

There are musicians who constantly reinvent themselves, “chameleons” as the critics like to call them. On the other hand, we find those who are always recording the same album but with different titles. What does our curator think of this dichotomy? “It’s always difficult to create. It comes out of your gut. There are projects that take months to come out, because I don’t have the right angle; I think that’s also the case with musicians or writers who have a certain audience. People are waiting for an evolution or a very big contrast. There’s old music that’s very topical. Bonga is suddenly current, within this movement of the new Lisbon. I’ve always seen projects like this. How many jazz records from the 50s, 60s don’t sound fresh nowadays?”

Is timelessness the great goal of any creative project? To be beyond time? “It would be a good goal. It’s to feel the time, here and now. There are geniuses who can do it. João Barbosa (Branko) is someone who is always looking for new paths and feeling the vibration of the city.” Ricardo snaps his fingers again and tells us a story about Miles Davis. “When he creates the album Doo Bop (1992) he enters into hip hop, and in an interview, he says ‘I put my head out of the window and this was the rhythm of the city.’ It is a question of sensitivity and feeling the moment, the way you cross information and create something remarkable, it’s something that needs – once again – time. You have to live, you have to listen… you don’t become a genius from one day to the next. A Picasso, a Miles Davis, is a continuous evolution.”

After Doo-Bop we go back to 1975, to talk about another great jazz album, one of the best sellers in history: The Köln Concert, which accompanies Ricardo when he needs time. “I’ve heard it hundreds of times. At times when I’m writing and can’t hear anything with lyrics. I’ve listened to it when I’m sad, when I need something that roots me, or when I want to be out of my head and lose myself in music.” At this point in the conversation, a client from the coffee shop where we are sitting settles at the piano that is less than a meter away from us, and begins to play almost as intensely as Keith Jarrett those 44 years ago, in Cologne, as if he was making sure to give us the right soundtrack at the right moment. “It’s an unbelievable album that was given to me by a friend, my English literature teacher at university, Ângela Prestes, who had been at that concert. That record – during a trip, it can be rainy or sunny, if you hear it from beginning to end, you don’t notice the time passing. This album takes you out of the moment.”

To be a Portuguese musical curator in 2019 is, more than ever, to be attentive to the moment. “Portugal is in fashion, and in cycle with more agitated societies. All these startups come to this little country by the sea, have our Mediterranean diet, live minutes away from the beach… We’re the right country, at the right time, on the right trend. Portugal can teach the rest of the world to slow down.”

What Ricardo has been doing, whether at parties in the village of Soutocico, at Lux or in a living room near you, is intertwining and sharing an experience of what he has heard and observed, here and there, from Sunday to Thursday. “This question of having time for the other is what’s most relevant.” And then, regarding the death of a friend – a member of a sort of hippie community to which Ricardo belongs – he raised the question, “How long do we really give ourselves to others. How much time do we need to get to know each other better? We can’t go on and on in this frenzy of wanting everything, but being nothing. The mutual help of the community is something that we have to value more.”

Ricardo Lopes did not live in the 1960s, doesn’t have hair that goes past his shoulders, never mentioned names like Janis Joplin or Jimi Hendrix, and never launched the phrase “peace and love,” but nonetheless, during the hour and twenty-four minutes that we spent together in the Menina e Moça bookshop, he referred countless times – passionately – to the importance of the mutual support that he finds in their communities, as if he were a hippie at heart.

“Connection, and not a digital one, is something that we have to value more.”

The son of candy and pastry manufacturers from the Leiria region, from an early age he would have learned the best recipes for combining people, music, contexts, and brands – even if he hadn’t later studied and worked in marketing and advertising. There are those who call him an organizer of cultural events, a musical curator, or one of the two heads behind the Lisbon Living Room Sessions, but he is no longer an ad-man. His rhythm is different now, with more time, more longevity, and more finger-snapping.

"The absence of hurry makes projects more solid."

"Nothing is done, nothing is consolidated, in a hurry."

"You have to live, you have to listen… You don’t become a genius from one day to the next."

"It’s important to turn off for a few moments, to allow you to be with yourself."

"We’re the right country, at the right time, with the right tendency. Portugal can teach the rest of the world to slow down."

"How much time do we really give ourselves to others?"

"We can’t keep going continuously in this frenzy of wanting everything, but being nothing."

We met at the Menina e Moça bookshop, on the vibrant pink street of Cais do Sodré, in Lisbon. Curiously, it was in this space – while its name was still Velha Senhora – that the project Ricardo has been working on for more than four years began. That night, frustrated by the noise of an office Christmas dinner, Ricardo and Joanna Hecker (also a Slow Forward ambassador) agreed to experiment with a project that creates space for listening to music in an intimate way – and without Secret Santas. The first Lisbon Living Room Session happened the following month, on January 25, 2015, with Diego el Gavi and his band – the very same musicians that Joanna and Ricardo could barely hear in Velha Senhora.

Let’s go back to Leiria, to the time when the Hidromel Factory – and the confectionery of the same name – distributed sweets throughout the country and employed about 200 people. “The factory was 7 kilometers from Leiria, in my mother’s hometown of Soutocico, which means a group of little chestnut trees.” Ricardo’s parents became important people in the region, and not only because of what they produced: “When you have a company with 200 employees, not only do you have relevance in economic terms, but also social terms.”

The factory was divided into several sectors. There were the candies, transversal across the entire year. But then, season by season, there was the canned fruit section, the candied fruits, the marmalades, the suckers, the Easter almonds, the cookies, and the “bolos-rei”, sold all over the place, and offered and personally delivered to the students of the prison school of Leiria on Christmas Eve. “I remember stealing peaches from the assembly line, already cut in half and pitted” rescued from a life in syrup. “During the holidays I used to use a forklift to load trucks. If you’re the boss’s son, you have to work. The house was in front of the factory and sometimes my friends were in the pool and I was working.”

Ricardo has never played any instrument. He has always been more in the production mode. “I remember a band of friends from high school who played heavy rock. Their band name was Ukurralle and they did a rehearsal, recorded it in the empty pool at my house. Birthday parties were always big and memorable. I think my route to production started there. It’s about knowing how to receive. How do you receive people at home? It was something I learned from my parents.”

In 1997, the year his father died, Ricardo went to Lisbon to study, and two years later he met “DJ Johnny, during one of those crazy Lux nights, that lasted until lunchtime the next day listening to vinyl at his house.”

Between the first and second squads of the CoolTrain Crew (a group of DJs and drum-and-bass musicians), Ricardo began to move around with a group that would become fundamental for new dance music in Portugal. “It was during the first generation – Johnny, Dinid, Tiago Miranda, MC Knowledje, Vítor Belanciano, Nuno Rosas, Rui Murka – and the beginning of the second generation, with João Barbosa (a.k.a. Lil’John a.k.a. Branko), Kalaf, Rui Pité (DJ Riot) and Alex Talhinhas, from Macacos do Chinês. Johnny plays an almost mentor-like role in our generation, someone with a deep knowledge of various musical genres who thought of the freshness of music as something timeless, but also as a cultural movement. He is a creator by nature.”

In 2003 Ricardo and Johnny launched the Leiria Jazz Sessions, “every Sunday for two years, taking jazz to downtown Leiria. The idea was to deconstruct the preconceived idea that jazz is all free jazz, with each musician playing for himself.”

The sessions showed Leirians how jazz influenced so many other genres (from hip hop to drum and bass, from soul to funk and bossa nova, from rock to reggae) or has common roots with music from Mali and the West African coast. “We took swing, standards, Latin American music project, afro-beat and new Portuguese authors. We tried to bring the best musicians of that generation – André Fernandes, Nelson Cascais, André Sousa Machado, Bruno Pedroso, David Biney, Craig Taborn, among so many others.” The space was the Camões Brewery, in the center of the city, with a 170-seat capacity. “When we went forward they thought we were crazy: ‘How are they going to bring jazz to a provincial city that may be financially and economically rich, but is very poor culturally, on a Sunday, at 21:30, when people are watching television?’”

At that time, on one of the Sundays of each month, Johnny would play vinyl, João Barbosa would create a set, and an invited guest would come along to recite poetry. Antonio Tabucchi was responsible for bridging the gap between jazz icons and Portuguese literature, the first being Miles Davis with Fernando Pessoa (spoken word by Kalaf), Duke Ellington with Natália Correia and Charlie Parker in dialogue with José Cardoso Pires. “The fear dissipated and we were always full.” There was a special episode with a couple of civil servants. “They came to me after a few months to thank me for the fact that this was happening in Leiria, and then they say, ‘We already bought two jazz albums.’ I got curious and asked what they were. Sarah Vaughan was the first. Okay, it’s commercial, swing, easy to hear – but good. The second was Thelonious Monk. I thought, ‘my work is done.’ In other words, a musician who is not easy to listen to – complex – this couple made it there. Just like I did, and still do my course, they can also do theirs. That’s the motive, the role as a musician or cultural agent.”

The great majority of his ongoing music projects take time to prepare, time to take root, time to grow – but in advertising, it’s all the opposite, all quick, all to be done by yesterday, and all to forget. “The absence of hurry makes projects more solid. Nothing is done, nothing is consolidated in urgency. We see constant ephemeral phenomena that are the best, the greatest, everything due tomorrow, everything with a great machine behind it, but the ones that have longevity are rare.”

What began in Leiria and then moved on to the Lisbon Jazz Sessions (at the Bicaense bar), the Lux Frágil Jazz Sessions, the Lisbon Living Room Sessions, and Fado Redux concerts, among other projects, was a growing path in adaptation to the environment and in the creation of small tribes of believers. “The habits help to create a sense of belonging and learning step by step, without being in a hurry. People know that the quality is there, that they can count on the moment today or next week or next month.”

In his musical projects Ricardo crosses several areas and creative heads, including musicians, DJs, writers, illustrators and photographers “to create a product, it has to make sense as a whole, people are waiting for references and anchors that can teach them something.”

It’s extremely important to know, “When you live in society and in a community, what is our role? Are we just here to receive, like consumers? Are we waiting for others to serve us, for the parish council or the town council or the government to take care of everything? Or can we also do something, at our own scale? And how can this have an impact on our community? That’s how all of the projects were born: with sharing, intervention, a certain slowness, but that really create a community.”

And the results in the community, are they palpable? “I feel recognition. One thing is the community of your street, your neighborhood, your city. Projects may be small, but they’re full houses. People are passionately there. With friends, passing the word. But there’s a gap between the people who do things with passion, where there’s not merely a financial aspect and the marketing approaches that don’t know what’s on the street or the journalists who don’t leave the newsroom.”

A lot of people are too busy to pay attention to the genesis of certain movements. “We live behind a screen, we walk down the street on headphones, we don’t have time for others, we don’t pay attention, we don’t get involved…”

What do you do to stop? “I travel. I disconnect completely.” And in Lisbon? “I don’t use headphones in the city, I try to listen to the rhythms of the city when I walk. I go out at night to listen to music, especially from Sunday to Thursday. Sometimes I go to places that nobody remembers, but there’s a musician I’ve never seen live, in a place that can be interesting – and this combination, on a Tuesday night… I’ve had so many unbelievable encounters that if I don’t try, don’t go, don’t get involved, they don’t happen.”

Ricardo obliges himself to explore unknown territories, almost like a mission: it is “a continuous curiosity,” which allows him to be his own novelty dealer, in 90% of cases. The idea is to understand if a band or musician can communicate with the public. “I remember Keziah Jones, a Nigerian musician, a reference in the Lisbon Living Room Sessions. When we were two years old, it was from that point on that we went beyond the underground of our friends.” Ricardo also remembers that the journalists woke up to the project because they thought, “‘How does a name like Keziah Jones play in a living room in Lisbon?’ There’s a very long delay, but you think, you’ve had this information for a long time, it didn’t have to be Keziah, it could have been António or Manel… Pay attention, have the experience, come and see.”

“I find him at the door of Bela, the tasca in the Rua dos Remédios where I go regularly to support other curators like Carlos Mil-Homens. And on a normal night of drinking, music, and friends, Keziah Jones appears with his hat on. I couldn’t remember his face and we started talking until somebody asked me who he was.”

Once Ricardo realized who he had in front of him, he didn’t waste any time in inviting him to the next L.L.R.S. session, and the musician accepted. “This happens when there are familiarity and trust, when they realize that people on the other side are real and do things with passion. Then relationships become intimate concerts, unique and unrepeatable, with news on Público and Expresso… Another thing Keziah said to me, which also has to do with time and authenticity, was that when he played a meter away from the audience, in a full living room, hot as hell, he thought: ‘here there are no tricks, you’re a street musician, either you know it or you don’t know it.’”

Intimacy, proximity, trust, and longevity are what Ricardo seeks in his projects, whether they are developed by two, four or more hands. In the midst of his work he travels, just as he did during the trip that was supposed to be three months – with only a one-way flight to Argentina – and ended up lasting two years. “It’s important to turn off a few moments to allow you to be with yourself.”

“Journeys like I do them, are unscheduled. I have a maxim, that is: When I start to get too comfortable *snaps fingers* I have to take off. I can’t put down roots. It’s about getting out of the comfort zone continuously.”

Which cultures can teach us the best ways to deal with time? “The countries that have marked me most are Buddhist cultures, a calmer culture that respects the time and space of each one. It can be seen in countries like Burma. I think it has to do with the delicacy of how they treat one another, but also with the fact that they are not so technologically advanced. They dedicate time to others, they want to get to know you, they’re willing to share, whether it’s a bed, a plate of food or a conversation.”

There are musicians who constantly reinvent themselves, “chameleons” as the critics like to call them. On the other hand, we find those who are always recording the same album but with different titles. What does our curator think of this dichotomy? “It’s always difficult to create. It comes out of your gut. There are projects that take months to come out, because I don’t have the right angle; I think that’s also the case with musicians or writers who have a certain audience. People are waiting for an evolution or a very big contrast. There’s old music that’s very topical. Bonga is suddenly current, within this movement of the new Lisbon. I’ve always seen projects like this. How many jazz records from the 50s, 60s don’t sound fresh nowadays?”

Is timelessness the great goal of any creative project? To be beyond time? “It would be a good goal. It’s to feel the time, here and now. There are geniuses who can do it. João Barbosa (Branko) is someone who is always looking for new paths and feeling the vibration of the city.” Ricardo snaps his fingers again and tells us a story about Miles Davis. “When he creates the album Doo Bop (1992) he enters into hip hop, and in an interview, he says ‘I put my head out of the window and this was the rhythm of the city.’ It is a question of sensitivity and feeling the moment, the way you cross information and create something remarkable, it’s something that needs – once again – time. You have to live, you have to listen… you don’t become a genius from one day to the next. A Picasso, a Miles Davis, is a continuous evolution.”

After Doo-Bop we go back to 1975, to talk about another great jazz album, one of the best sellers in history: The Köln Concert, which accompanies Ricardo when he needs time. “I’ve heard it hundreds of times. At times when I’m writing and can’t hear anything with lyrics. I’ve listened to it when I’m sad, when I need something that roots me, or when I want to be out of my head and lose myself in music.” At this point in the conversation, a client from the coffee shop where we are sitting settles at the piano that is less than a meter away from us, and begins to play almost as intensely as Keith Jarrett those 44 years ago, in Cologne, as if he was making sure to give us the right soundtrack at the right moment. “It’s an unbelievable album that was given to me by a friend, my English literature teacher at university, Ângela Prestes, who had been at that concert. That record – during a trip, it can be rainy or sunny, if you hear it from beginning to end, you don’t notice the time passing. This album takes you out of the moment.”

To be a Portuguese musical curator in 2019 is, more than ever, to be attentive to the moment. “Portugal is in fashion, and in cycle with more agitated societies. All these startups come to this little country by the sea, have our Mediterranean diet, live minutes away from the beach… We’re the right country, at the right time, on the right trend. Portugal can teach the rest of the world to slow down.”

What Ricardo has been doing, whether at parties in the village of Soutocico, at Lux or in a living room near you, is intertwining and sharing an experience of what he has heard and observed, here and there, from Sunday to Thursday. “This question of having time for the other is what’s most relevant.” And then, regarding the death of a friend – a member of a sort of hippie community to which Ricardo belongs – he raised the question, “How long do we really give ourselves to others. How much time do we need to get to know each other better? We can’t go on and on in this frenzy of wanting everything, but being nothing. The mutual help of the community is something that we have to value more.”

RicardoLopes

Listening without headphones

Interviewed in the Menina e Moça Bar, in Lisbon.

Ricardo Lopes did not live in the 1960s, doesn’t have hair that goes past his shoulders, never mentioned names like Janis Joplin or Jimi Hendrix, and never launched the phrase “peace and love,” but nonetheless, during the hour and twenty-four minutes that we spent together in the Menina e Moça bookshop, he referred countless times – passionately – to the importance of the mutual support that he finds in their communities, as if he were a hippie at heart.

“Connection, and not a digital one, is something that we have to value more.”

The son of candy and pastry manufacturers from the Leiria region, from an early age he would have learned the best recipes for combining people, music, contexts, and brands – even if he hadn’t later studied and worked in marketing and advertising. There are those who call him an organizer of cultural events, a musical curator, or one of the two heads behind the Lisbon Living Room Sessions, but he is no longer an ad-man. His rhythm is different now, with more time, more longevity, and more finger-snapping.

"The absence of hurry makes projects more solid."

"Nothing is done, nothing is consolidated, in a hurry."

"You have to live, you have to listen… You don’t become a genius from one day to the next."

"It’s important to turn off for a few moments, to allow you to be with yourself."

"We’re the right country, at the right time, with the right tendency. Portugal can teach the rest of the world to slow down."

"How much time do we really give ourselves to others?"

"We can’t keep going continuously in this frenzy of wanting everything, but being nothing."

We met at the Menina e Moça bookshop, on the vibrant pink street of Cais do Sodré, in Lisbon. Curiously, it was in this space – while its name was still Velha Senhora – that the project Ricardo has been working on for more than four years began. That night, frustrated by the noise of an office Christmas dinner, Ricardo and Joanna Hecker (also a Slow Forward ambassador) agreed to experiment with a project that creates space for listening to music in an intimate way – and without Secret Santas. The first Lisbon Living Room Session happened the following month, on January 25, 2015, with Diego el Gavi and his band – the very same musicians that Joanna and Ricardo could barely hear in Velha Senhora.

Let’s go back to Leiria, to the time when the Hidromel Factory – and the confectionery of the same name – distributed sweets throughout the country and employed about 200 people. “The factory was 7 kilometers from Leiria, in my mother’s hometown of Soutocico, which means a group of little chestnut trees.” Ricardo’s parents became important people in the region, and not only because of what they produced: “When you have a company with 200 employees, not only do you have relevance in economic terms, but also social terms.”