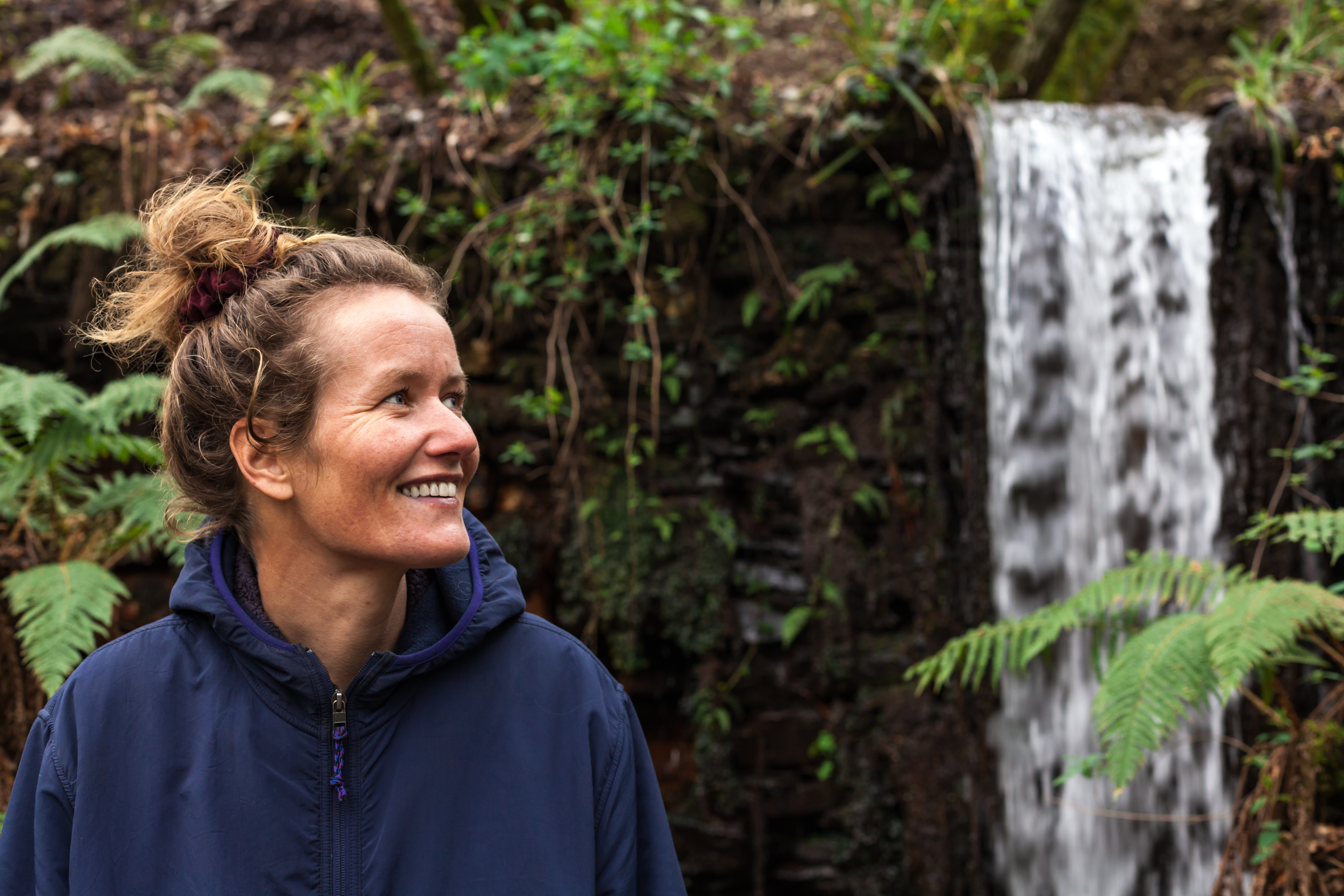

FranciscaGorjão Henriques

Interviewed on May 8 2019 during lunch at the community table at Mezze, Arroios Market, in Lisbon.

The mystery of the leafless birch tree

Francisca Gorjão Henriques is a freelance journalist, the fifth of six children, president of the Associação Pão a Pão (which runs the Mezze restaurant, staffed primarily by Syrian refugees) and has an ability that is rare in these hurried times: she is able to sit on the sofa in her house and do nothing for a long time, without books, without a mobile phone, without any distractions beyond the trees in her garden. She learned to petrify a little with Japanese stone gardens, but the first great brakes to slow her life happened to her at the age of 26 in the form of her first daughter, Laura.

Today, at the age of 47, she lives at two tempos: in a hurry, slow, slow, and in a hurry. Our conversation took place without clocks or interruptions, on the communal table at Mezze, with bread, food, drink, aromas, laughter and noises in the mix. When we finally left the table, shaking words from our chests, the restaurant was empty with the exception of the staff preparing for the upcoming dinner rush.

"In a stone garden nothing moves: it is total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly."

"I live at my own speed."

"It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotions."

"When my daughter was born I often said that she was the materialization of time. Through her I could see time passing."

"I am perfectly capable of sitting on the sofa and doing nothing for a long time. Without picking up a mobile phone, a book, nothing."

"Apparently handwriting is an archaic thing."

"People dedicating themselves entirely to something and doing it as well as possible (...) is something that moves me."

"There is a kind of knowledge attached to the earth that is very little valued."

In 20 years of interviews, reports, and articles for the newspaper Público, there’s a story loaded with idleness. Featuring the Via Algarviana road, which she walked for twelve days, the story gives its message: “You don’t get anywhere fast, because that word doesn’t exist when you walk a road like this.” Let us walk, then. “I love to walk and I still remember that story often.” At the beginning of her professional life, Francisca was in the spotlight in the area of international politics, specialized in the East. Did the Eastern peoples help her to tame the typical speed of everyday life in the West? “I wish I had learned much more. Each time I went to do 20 reports in 4 days. I spent longer periods there, but in fact it was always very intense work, with no time to breathe. But one of the stops, in Tokyo, took me to one of those wonderful stone gardens and suddenly you really feel a break. Even more than looking at a tree, where there’s always the wind shaking the leaves or branches – or at a field where the flowers sway – in a stone garden nothing moves, it’s total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly.”

At that time, Francisca was not yet convinced of the need to slow her rhythm: “This hypothesis only came later. It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotion. When we’re starting a project or learning a profession, there’s a certain voracity. If there isn’t one, it’s a bad sign. We want to experience everything and give it our all. We feel that we have to take advantage of the moments for learning; then you want to produce, and show that you’ve learned, and that now you’re doing better than you did two months ago.”

Would the 47-year-old Francisca have something to do with the 27-year-old Francisca, if they met at a temporal crossroads? “I’d tell her to take it easy. But my younger version probably wouldn’t listen, because things have their own time, right?”

Does motherhood bring a new sense of time? “It’s very funny. When my daughter was born, I often said that she was the materialization of time. Through her, I could see time passing. Because when you are 26, 28, 38 years old, you are the same person, while children change from day to day, from week to week. You see time materializing, which impressed me immensely.”

Knowing the other through journalism, family and immigration are three frontlines of Francisca’s work. “The other is actually me. Mário de Sá-Carneiro used to say, ‘I’m not me and I’m not the other, I’m something in between.’ Ultimately you don’t do anything that isn’t in you to do. If suddenly I find myself involved with a project of integration with refugees from the Middle East it’s because that impulse is in me.”

Francisca believes that those who have a privileged life – that is, without the urgent need to survive – can, at the very least, help others. And from here we set out for the only rehearsed part of our conversation, the one that has already been repeated to many interviewers, in which she explained to us how the walls were built around two hands holding Syrian refugees.

The idea was born from a conversation, at lunch, “between me and some friends; after that conversation, not doing it would seem almost immoral”. The designer Rita Melo and the architecture student Alaa (a young Syrian staying with Francisca’s family) were among the interlocutors. When Alaa confessed that her greatest dose of nostalgia had to do with bread from Syria, they first found it strange that there was no Arab bread in Lisbon and thought of opening a bakery. “We moved on to the restaurant because the bread gets everything onto the table, and there’s no point in eating this bread with cheese, as we Portuguese do. And we even found the idea of the restaurant funny. In this case, what it adds is that we also find work for the people who are arriving, and we take advantage of such a rich part of their identity, that can be shared with their host community.”

According to this interviewer-turned-interviewee, in Portugal there is no inertia when it comes to showing solidarity, but “sometimes people don’t know very well how to help. Because it’s difficult. The system is not set up so that people have time to get involved in civic, political and associative projects.” How will that time have to be conquered? Francisca bets on a new attitude of the private sector, or even on quotas of time for community service. “Anything, five hours a month – your time would be devoted to the community. Some companies have banks of hours that employees can use. Instead of being at work in front of the computer, they can use those hours to volunteer. I think this is very good. Volunteering is a bit trendy and sometimes there’s a bit of an overkill around you. But it’s better to sin by excess than by lack.”

We wanted to know if the new position of freelance journalist brought a new speed to Francisca’s life. “No. In fact, even my son complains and says ‘Mum used to say that she would have plenty of time for me when she left Público, and after all, she has nothing.’ I don’t live at another speed, but I live at my own speed.”

João’s mum’s life is not necessarily slower, but there are slow phases, alternating with faster phases. Francisca won her right to moments of leisure. “Managing your own time is a luxury. I look at my own schedule and say that on this day I can’t meet someone because I have to take my son to the conservatory, I’ll meet on the next day. To be able to do this is very good.”

I wondered what Francisca does when she wants to stop. “I’m lucky enough to live in an absolutely wonderful place.” From her house, in Penedo, in Colares, you can see the Serra de Sintra and feel the Atlantic breeze. “I am perfectly capable of sitting on the sofa and doing nothing for a long time. Without picking up a mobile phone, a book, nothing. That birch is still without leaves this year; what’s happening to it? The elm tree already has leaves; the birch should have leaves earlier; why does it still not have leaves?”

Born and raised in the capital, Francisca grew up completely urban, far from the pack saddle. “I lived in Lisbon and spent my holidays in Ericeira, which also isn’t a rural area. The exception was late summer. My mother used to organize picnics with donkey rides near Ericeira, and we would pick blackberries to make jam.”

Her maternal grandparents had a home in Ericeira and Francisca still remembers meeting an artist who had never uprooted her own imagination from the village, the painter Paula Rego. Meanwhile, there were two revolutions in the Gorjão Henriques family. “The older kids grew up quite differently: we are 6, and there have always been the 3 older ones and the 3 younger ones. And the thing that marks this boundary was 25 April, and my parents’ separation two years later.”

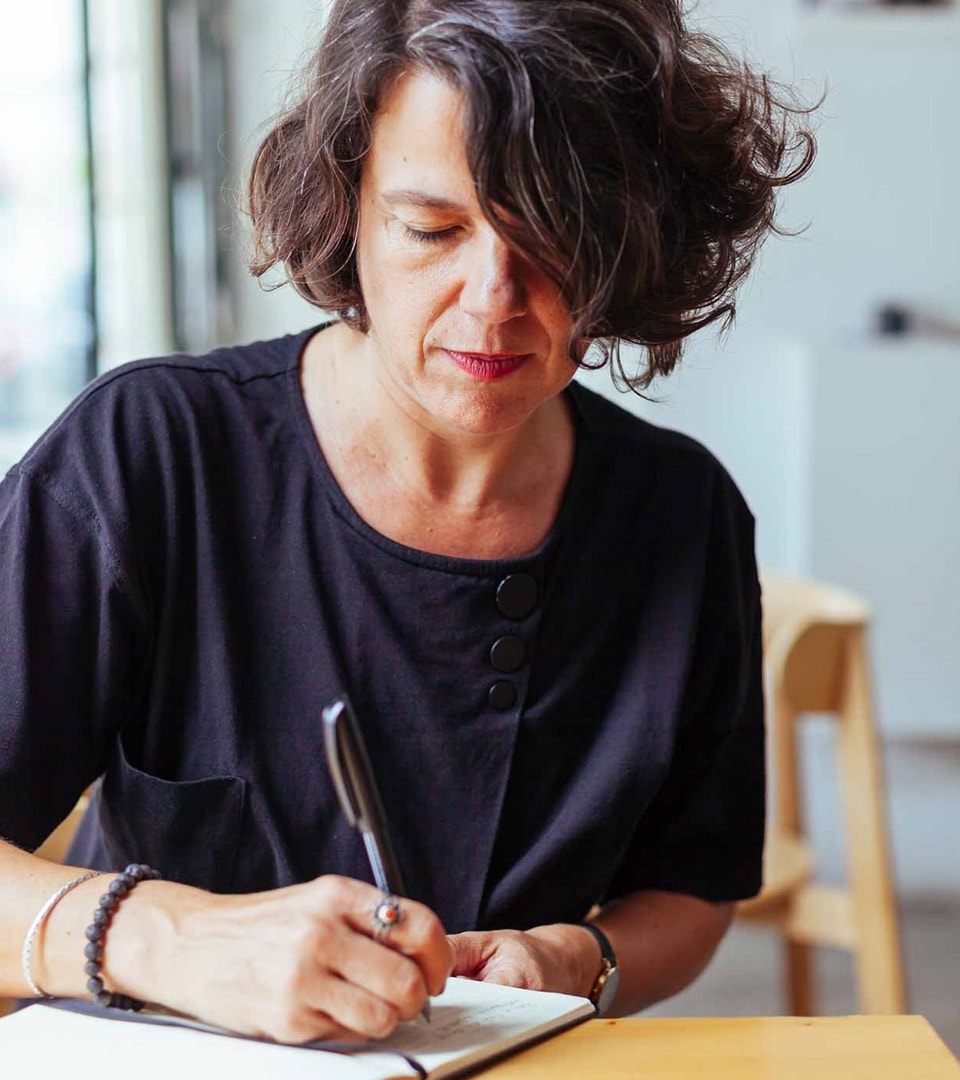

Speaking of other times, we wanted to know what the journalist insists on continuing to do, as in olden days. Write by hand? “Write by hand, yes. Some time ago, I was at (the magazine) Fugas and I went to interview Gordon Ramsay, and they also invited some bloggers and instagrammers. However, in addition to the interview there was a workshop to learn how to make beef Wellington, his signature dish. I was taking notes with my notebook and pen and the instagrammers, all in their twenties, look at me and say, ‘Oh how funny you write on paper!’ (laughs) It was one of the professional moments when I felt the most old-fashioned. For them everything is on the mobile phone: it’s immediately available and it’s easily editable. Apparently handwriting is an archaic thing.”

From beef Wellington we move on to pork cheeks, which take four hours to make. It’s not her signature dish, but it would be if, in a parallel world, Francisca were the chef. You can tell she is a methodical cook. “There is a Thai soup that I make very well, full of lemongrass and lime leaves. I bought a kafer grill on purpose to make Thai food; it’s indoors to hold a little more heat.”

Is cooking for friends and family one of the best ways to give these people our time? “Yes, it’s a commonplace to say that it’s a gesture of love; what it really is is a gesture of surrender. I’m the fifth of six children and it’s always been normal to have dinners with a lot of people, so I like having people at home a lot. I don’t feel it’s a big mission.”

Is it true that, at the table, no one grows old? “At the table we deal with everything, for better and for worse. We really like to talk about sharing, conversation, having long lunches that last all afternoon, but sometimes it’s also the other way around. You sit in front of a person, during the time that you’re there, and maybe that’s the moment when you’re going to try to set things onto clean plates. Eh? On clean plates! Friendships are created and broken, relationships are made and unmade. Obviously it’s more pleasant to look at the thing from a more positive side, to see the table as the place to share, which is the ideal. If we think of places of communion with others, there is no other place as powerful as the table. It becomes something that you really ingest. For some reason, communion in the church involves giving the host to the believer, doesn’t it? It’s the symbolic bread. These terms exist and I’m thinking out loud. At this very moment, this makes sense to me.”

At the risk of asking a question like “What do your eyes say?,” since she works with other people’s restlessness we wanted to know what worries Francisca. “I am very worried about intolerance and inequality. I find it incomprehensible how people living in the 21st century, with access to information, are capable of intolerance. How does that happen to them? Of course we can explain – the fear, the security, the populist discourse that feeds all of these things – but from that moment when you meet the one whom you think of as The Other, you realize that it’s a person who has exactly the same problems that you have. Reconciling life at home with life at work, catching the same transport, wishing for a job that’s fulfilling, hoping to be able to send your kids to university. In short, we are equal. This is evident, but this is the way it is, and because it’s true, it worries me.”

And what quiets Francisca’s nerves? The answer, in the middle of a laugh, was that “music quiets me.”

How do you build in time for others? “This is all out of selfishness. It’s not to feel good in a moral sense, ‘Ah, this is not right, let’s make it right.’ It’s to feel good, insofar as I have this restlessness and it soothes my restlessness. It doesn’t make sense to have children if we don’t want to share things with them, and to live their things, nor does it make sense to work only for yourself. I’m in a project where the relationship with others is very direct, right? It’s about integration. But in fact, even as a journalist, a story is always to be shared with someone. What we do, we almost always do for ourselves, from one point of view or another, either because we really feel good to do it or it fulfills us in some way, or because our moral or ethical conscience tells us that it’s the right thing to do. It’s still our imperative.”

Throughout her journey, Francisca has met several wise men of the earth who stick in her memory. Could we call them “farmers?” “People dedicating themselves entirely to something and doing it as well as possible and knowing everything there is to know about that specific thing is something that moves me. There are very few people like that. I feel that there is a kind of earthbound knowledge that is very little valued. You consider someone cultured who knows how to talk about cinema, literature, music, history, geography… but then you don’t need to know how to distinguish a plum tree from a pomegranate tree. Why?”

“I met Mário Neves on the island of Pico, a man who knows everything about his land. He’s able to build a boat, catch the biggest fish, knows exactly the right seasons, which side of the canal the fish pass through, knows how to tell you all about the corn he grows, about the potatoes, about all of the animals around him. But will anyone say, ‘this gentleman is so cultured’? Nobody – but this is a wise man.”

It’s rare for a journalist to be calm about doing her job; the appreciation of time and hedonistic slowness is something that belongs more to the writers of novels. But Francisca already had the right to a story that – between fieldwork and writing – took almost 18 days.

“There was this story when time was a fundamental issue, at all levels. It was a report about the Via Algarviana road, called ‘The Algarve is Not Here.’ It’s a walk between Alcoutim and Sagres, and it takes 14 days. I only managed to do 12, from one end to the other, minus two legs of the journey. In addition to the Via Algarviana, I took a few detours to talk to a lady who weaves palm grass into baskets, and the last man making pack saddles for donkeys. I went with a guide because I was also interested in having an interpretation of the territory. I don’t know how to look and see, ‘here are the wild orchids, they only bloom in March…’ It would be a shame not to go with someone who could point me to those things. The story may seem prosaic to most people, but it sticks with me still today.”

Let us stop here. Francisca must go home and think about the leafless birch in her garden.

Francisca Gorjão Henriques is a freelance journalist, the fifth of six children, president of the Associação Pão a Pão (which runs the Mezze restaurant, staffed primarily by Syrian refugees) and has an ability that is rare in these hurried times: she is able to sit on the sofa in her house and do nothing for a long time, without books, without a mobile phone, without any distractions beyond the trees in her garden. She learned to petrify a little with Japanese stone gardens, but the first great brakes to slow her life happened to her at the age of 26 in the form of her first daughter, Laura.

Today, at the age of 47, she lives at two tempos: in a hurry, slow, slow, and in a hurry. Our conversation took place without clocks or interruptions, on the communal table at Mezze, with bread, food, drink, aromas, laughter and noises in the mix. When we finally left the table, shaking words from our chests, the restaurant was empty with the exception of the staff preparing for the upcoming dinner rush.

"In a stone garden nothing moves: it is total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly."

"I live at my own speed."

"It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotions."

"When my daughter was born I often said that she was the materialization of time. Through her I could see time passing."

"I am perfectly capable of sitting on the sofa and doing nothing for a long time. Without picking up a mobile phone, a book, nothing."

"Apparently handwriting is an archaic thing."

"People dedicating themselves entirely to something and doing it as well as possible (...) is something that moves me."

"There is a kind of knowledge attached to the earth that is very little valued."

In 20 years of interviews, reports, and articles for the newspaper Público, there’s a story loaded with idleness. Featuring the Via Algarviana road, which she walked for twelve days, the story gives its message: “You don’t get anywhere fast, because that word doesn’t exist when you walk a road like this.” Let us walk, then. “I love to walk and I still remember that story often.” At the beginning of her professional life, Francisca was in the spotlight in the area of international politics, specialized in the East. Did the Eastern peoples help her to tame the typical speed of everyday life in the West? “I wish I had learned much more. Each time I went to do 20 reports in 4 days. I spent longer periods there, but in fact it was always very intense work, with no time to breathe. But one of the stops, in Tokyo, took me to one of those wonderful stone gardens and suddenly you really feel a break. Even more than looking at a tree, where there’s always the wind shaking the leaves or branches – or at a field where the flowers sway – in a stone garden nothing moves, it’s total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly.”

At that time, Francisca was not yet convinced of the need to slow her rhythm: “This hypothesis only came later. It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotion. When we’re starting a project or learning a profession, there’s a certain voracity. If there isn’t one, it’s a bad sign. We want to experience everything and give it our all. We feel that we have to take advantage of the moments for learning; then you want to produce, and show that you’ve learned, and that now you’re doing better than you did two months ago.”

Would the 47-year-old Francisca have something to do with the 27-year-old Francisca, if they met at a temporal crossroads? “I’d tell her to take it easy. But my younger version probably wouldn’t listen, because things have their own time, right?”

Does motherhood bring a new sense of time? “It’s very funny. When my daughter was born, I often said that she was the materialization of time. Through her, I could see time passing. Because when you are 26, 28, 38 years old, you are the same person, while children change from day to day, from week to week. You see time materializing, which impressed me immensely.”

Knowing the other through journalism, family and immigration are three frontlines of Francisca’s work. “The other is actually me. Mário de Sá-Carneiro used to say, ‘I’m not me and I’m not the other, I’m something in between.’ Ultimately you don’t do anything that isn’t in you to do. If suddenly I find myself involved with a project of integration with refugees from the Middle East it’s because that impulse is in me.”

Francisca believes that those who have a privileged life – that is, without the urgent need to survive – can, at the very least, help others. And from here we set out for the only rehearsed part of our conversation, the one that has already been repeated to many interviewers, in which she explained to us how the walls were built around two hands holding Syrian refugees.

The idea was born from a conversation, at lunch, “between me and some friends; after that conversation, not doing it would seem almost immoral”. The designer Rita Melo and the architecture student Alaa (a young Syrian staying with Francisca’s family) were among the interlocutors. When Alaa confessed that her greatest dose of nostalgia had to do with bread from Syria, they first found it strange that there was no Arab bread in Lisbon and thought of opening a bakery. “We moved on to the restaurant because the bread gets everything onto the table, and there’s no point in eating this bread with cheese, as we Portuguese do. And we even found the idea of the restaurant funny. In this case, what it adds is that we also find work for the people who are arriving, and we take advantage of such a rich part of their identity, that can be shared with their host community.”

According to this interviewer-turned-interviewee, in Portugal there is no inertia when it comes to showing solidarity, but “sometimes people don’t know very well how to help. Because it’s difficult. The system is not set up so that people have time to get involved in civic, political and associative projects.” How will that time have to be conquered? Francisca bets on a new attitude of the private sector, or even on quotas of time for community service. “Anything, five hours a month – your time would be devoted to the community. Some companies have banks of hours that employees can use. Instead of being at work in front of the computer, they can use those hours to volunteer. I think this is very good. Volunteering is a bit trendy and sometimes there’s a bit of an overkill around you. But it’s better to sin by excess than by lack.”

We wanted to know if the new position of freelance journalist brought a new speed to Francisca’s life. “No. In fact, even my son complains and says ‘Mum used to say that she would have plenty of time for me when she left Público, and after all, she has nothing.’ I don’t live at another speed, but I live at my own speed.”

João’s mum’s life is not necessarily slower, but there are slow phases, alternating with faster phases. Francisca won her right to moments of leisure. “Managing your own time is a luxury. I look at my own schedule and say that on this day I can’t meet someone because I have to take my son to the conservatory, I’ll meet on the next day. To be able to do this is very good.”

I wondered what Francisca does when she wants to stop. “I’m lucky enough to live in an absolutely wonderful place.” From her house, in Penedo, in Colares, you can see the Serra de Sintra and feel the Atlantic breeze. “I am perfectly capable of sitting on the sofa and doing nothing for a long time. Without picking up a mobile phone, a book, nothing. That birch is still without leaves this year; what’s happening to it? The elm tree already has leaves; the birch should have leaves earlier; why does it still not have leaves?”

Born and raised in the capital, Francisca grew up completely urban, far from the pack saddle. “I lived in Lisbon and spent my holidays in Ericeira, which also isn’t a rural area. The exception was late summer. My mother used to organize picnics with donkey rides near Ericeira, and we would pick blackberries to make jam.”

Her maternal grandparents had a home in Ericeira and Francisca still remembers meeting an artist who had never uprooted her own imagination from the village, the painter Paula Rego. Meanwhile, there were two revolutions in the Gorjão Henriques family. “The older kids grew up quite differently: we are 6, and there have always been the 3 older ones and the 3 younger ones. And the thing that marks this boundary was 25 April, and my parents’ separation two years later.”

Speaking of other times, we wanted to know what the journalist insists on continuing to do, as in olden days. Write by hand? “Write by hand, yes. Some time ago, I was at (the magazine) Fugas and I went to interview Gordon Ramsay, and they also invited some bloggers and instagrammers. However, in addition to the interview there was a workshop to learn how to make beef Wellington, his signature dish. I was taking notes with my notebook and pen and the instagrammers, all in their twenties, look at me and say, ‘Oh how funny you write on paper!’ (laughs) It was one of the professional moments when I felt the most old-fashioned. For them everything is on the mobile phone: it’s immediately available and it’s easily editable. Apparently handwriting is an archaic thing.”

From beef Wellington we move on to pork cheeks, which take four hours to make. It’s not her signature dish, but it would be if, in a parallel world, Francisca were the chef. You can tell she is a methodical cook. “There is a Thai soup that I make very well, full of lemongrass and lime leaves. I bought a kafer grill on purpose to make Thai food; it’s indoors to hold a little more heat.”

Is cooking for friends and family one of the best ways to give these people our time? “Yes, it’s a commonplace to say that it’s a gesture of love; what it really is is a gesture of surrender. I’m the fifth of six children and it’s always been normal to have dinners with a lot of people, so I like having people at home a lot. I don’t feel it’s a big mission.”

Is it true that, at the table, no one grows old? “At the table we deal with everything, for better and for worse. We really like to talk about sharing, conversation, having long lunches that last all afternoon, but sometimes it’s also the other way around. You sit in front of a person, during the time that you’re there, and maybe that’s the moment when you’re going to try to set things onto clean plates. Eh? On clean plates! Friendships are created and broken, relationships are made and unmade. Obviously it’s more pleasant to look at the thing from a more positive side, to see the table as the place to share, which is the ideal. If we think of places of communion with others, there is no other place as powerful as the table. It becomes something that you really ingest. For some reason, communion in the church involves giving the host to the believer, doesn’t it? It’s the symbolic bread. These terms exist and I’m thinking out loud. At this very moment, this makes sense to me.”

At the risk of asking a question like “What do your eyes say?,” since she works with other people’s restlessness we wanted to know what worries Francisca. “I am very worried about intolerance and inequality. I find it incomprehensible how people living in the 21st century, with access to information, are capable of intolerance. How does that happen to them? Of course we can explain – the fear, the security, the populist discourse that feeds all of these things – but from that moment when you meet the one whom you think of as The Other, you realize that it’s a person who has exactly the same problems that you have. Reconciling life at home with life at work, catching the same transport, wishing for a job that’s fulfilling, hoping to be able to send your kids to university. In short, we are equal. This is evident, but this is the way it is, and because it’s true, it worries me.”

And what quiets Francisca’s nerves? The answer, in the middle of a laugh, was that “music quiets me.”

How do you build in time for others? “This is all out of selfishness. It’s not to feel good in a moral sense, ‘Ah, this is not right, let’s make it right.’ It’s to feel good, insofar as I have this restlessness and it soothes my restlessness. It doesn’t make sense to have children if we don’t want to share things with them, and to live their things, nor does it make sense to work only for yourself. I’m in a project where the relationship with others is very direct, right? It’s about integration. But in fact, even as a journalist, a story is always to be shared with someone. What we do, we almost always do for ourselves, from one point of view or another, either because we really feel good to do it or it fulfills us in some way, or because our moral or ethical conscience tells us that it’s the right thing to do. It’s still our imperative.”

Throughout her journey, Francisca has met several wise men of the earth who stick in her memory. Could we call them “farmers?” “People dedicating themselves entirely to something and doing it as well as possible and knowing everything there is to know about that specific thing is something that moves me. There are very few people like that. I feel that there is a kind of earthbound knowledge that is very little valued. You consider someone cultured who knows how to talk about cinema, literature, music, history, geography… but then you don’t need to know how to distinguish a plum tree from a pomegranate tree. Why?”

“I met Mário Neves on the island of Pico, a man who knows everything about his land. He’s able to build a boat, catch the biggest fish, knows exactly the right seasons, which side of the canal the fish pass through, knows how to tell you all about the corn he grows, about the potatoes, about all of the animals around him. But will anyone say, ‘this gentleman is so cultured’? Nobody – but this is a wise man.”

It’s rare for a journalist to be calm about doing her job; the appreciation of time and hedonistic slowness is something that belongs more to the writers of novels. But Francisca already had the right to a story that – between fieldwork and writing – took almost 18 days.

“There was this story when time was a fundamental issue, at all levels. It was a report about the Via Algarviana road, called ‘The Algarve is Not Here.’ It’s a walk between Alcoutim and Sagres, and it takes 14 days. I only managed to do 12, from one end to the other, minus two legs of the journey. In addition to the Via Algarviana, I took a few detours to talk to a lady who weaves palm grass into baskets, and the last man making pack saddles for donkeys. I went with a guide because I was also interested in having an interpretation of the territory. I don’t know how to look and see, ‘here are the wild orchids, they only bloom in March…’ It would be a shame not to go with someone who could point me to those things. The story may seem prosaic to most people, but it sticks with me still today.”

Let us stop here. Francisca must go home and think about the leafless birch in her garden.

FranciscaGorjão Henriques

The mystery of the leafless birch tree

Interviewed on May 8 2019 during lunch at the community table at Mezze, Arroios Market, in Lisbon.

Francisca Gorjão Henriques is a freelance journalist, the fifth of six children, president of the Associação Pão a Pão (which runs the Mezze restaurant, staffed primarily by Syrian refugees) and has an ability that is rare in these hurried times: she is able to sit on the sofa in her house and do nothing for a long time, without books, without a mobile phone, without any distractions beyond the trees in her garden. She learned to petrify a little with Japanese stone gardens, but the first great brakes to slow her life happened to her at the age of 26 in the form of her first daughter, Laura.

Today, at the age of 47, she lives at two tempos: in a hurry, slow, slow, and in a hurry. Our conversation took place without clocks or interruptions, on the communal table at Mezze, with bread, food, drink, aromas, laughter and noises in the mix. When we finally left the table, shaking words from our chests, the restaurant was empty with the exception of the staff preparing for the upcoming dinner rush.

"In a stone garden nothing moves: it is total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly."

"I live at my own speed."

"It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotions."

"When my daughter was born I often said that she was the materialization of time. Through her I could see time passing."

"I am perfectly capable of sitting on the sofa and doing nothing for a long time. Without picking up a mobile phone, a book, nothing."

"Apparently handwriting is an archaic thing."

"People dedicating themselves entirely to something and doing it as well as possible (...) is something that moves me."

"There is a kind of knowledge attached to the earth that is very little valued."

In 20 years of interviews, reports and articles for the newspaper Público, there’s a story loaded with idleness. Featuring the Via Algarviana road, which she walked for twelve days, the story gives its message: “You don’t get anywhere fast, because that word doesn’t exist when you walk a road like this.” Let us walk, then. “I love to walk and I still remember that story often.” At the beginning of her professional life, Francisca was in the spotlight in the area of international politics, specialized in the East. Did the Eastern peoples help her to tame the typical speed of everyday life in the West? “I wish I had learned much more. Each time I went to do 20 reports in 4 days. I spent longer periods there, but in fact it was always very intense work, with no time to breathe. But one of the stops, in Tokyo, took me to one of those wonderful stone gardens and suddenly you really feel a break.

Even more than looking at a tree, where there’s always the wind shaking the leaves or branches – or at a field where the flowers sway – in a stone garden nothing moves, it’s total immobility. You feel the suspension of time very strongly.”

At that time, Francisca was not yet convinced of the need to slow her rhythm: “This hypothesis only came later. It’s very easy to become addicted to speed; it brings emotion. When we’re starting a project or learning a profession, there’s a certain voracity. If there isn’t one, it’s a bad sign. We want to experience everything and give it our all. We feel that we have to take advantage of the moments for learning; then you want to produce, and show that you’ve learned and that now you’re doing better than you did two months ago.”